Using electricity to stimulate parts of the brain may ease motion sickness. A team at Imperial College London say trials on 20 people suggest the method could have a similar effect to drugs, but without the drowsiness. The mild current interferes with messages arriving from the part of the ear which controls balance.

Other scientists urged "healthy scepticism" until larger trials backed up the findings, reported in Neurology. Whether you are travelling by plane, boat or car, motion sickness is thought to be down to mixed messages coming from your ears and your eyes. It leaves the brain confused about what is going on and culminates in nausea and headaches.

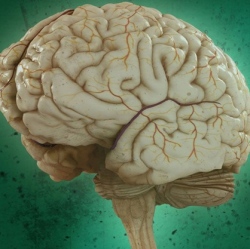

Dr Qadeer Arshad, from the movement and balance group at Imperial, said people no longer had motion sickness if their inner ear was damaged. So the team used "transcranial direct current stimulation" to try to manipulate the part of the brain that interprets messages coming from those balance organs in the ear while people were made to feel nauseous.

Twenty volunteers were placed in a "chunder chair" which is like a twisted fairground ride that spins someone round at an angle. It is guaranteed to make pretty much anyone motion sick within five minutes. Keep going and you will be physically sick, as some of the participants found out.

Then one hour later, half of the participants had small electrical currents passed through their scalp to alter their brain activity. The other half were given a dummy treatment. With the stimulation, it took an extra 207 seconds, on average, for motion sickness to develop.

Whereas those getting the dummy treatment actually felt nauseous 57s sooner (one bout of motion sickness makes you more vulnerable to another). The results showed the stimulation improved recovery times.

Dr Arshad told the BBC News website: "The best comparison is with the best known drug scopolamine – we showed in essence that it’s equivalent to scopolamine, but that drug knocks you out, it puts you to sleep." He said there were no known side-effects to brain stimulation and that it would be easy to develop.

"Within the next couple of years people will be able to use these devices – it’s not far away," he said. The group are also investigating brain stimulation for virtual and augmented reality devices, which can also result in headaches in some people, and for nausea after cancer chemotherapy.