Doctors are one step closer to a simple test that could predict whether a patient is about to have a heart attack — by using a blood sample to detect cells that have sloughed off of damaged blood vessel walls.

The finding, published Wednesday in the journal Science Translational Medicine, could potentially address "the greatest unmet need" facing cardiologists, said lead author Dr. Eric Topol, a cardiologist at the Scripps Translational Science Institute in San Diego. Though physicians can easily detect a heart attack that’s already underway, every year tens of thousands of patients walk away from the doctor’s office after having passed a stress test, only to suffer a devastating heart attack within a few weeks.

Topol called the phenomenon the "Tim Russert syndrome," referring to the newsman who died of a heart attack in 2008, weeks after undergoing a stress test with apparently normal results.

"When someone is having the real deal, we know that," Topol said. "The real question is, is something percolating in their artery? We’d like to prevent the heart attack from happening," or mitigate its effects with drugs.

The new technique involves tracking a type of cell in the blood called a circulating endothelial cell.

Endothelial cells create a wrapper that lines the inside of blood vessels. When the vessel is damaged, endothelial cells break away and enter the bloodstream.

Healthy people have very few of these circulating cells. But a person with mild cholesterol buildup can develop a crack in an artery wall that disrupts the lining and sends them into the blood.

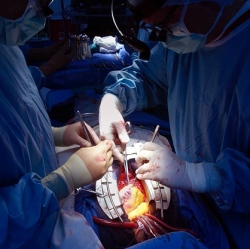

A heart attack occurs when an area of plaque ruptures in an artery, forming a blood clot that blocks blood flow to the heart, resulting in heart tissue damage.

Ruptures resulting from mild cholesterol buildups can lead to particularly deadly heart attacks, said Dr. Douglas Zipes, a cardiologist at the Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis, because patients with such blockages are often asymptomatic, and — unlike people with larger blockages — are unlikely to have developed new blood vessels that can help bypass the obstruction.