Scientists have begun testing a radically new approach to treating schizophrenia based on emerging evidence that it could be a disease of the immune system. The first patient, a 33-year old man who developed schizophrenia, was treated at King’s College Hospital in London.

During the next two years, 30 patients will receive monthly infusions of an antibody drug currently used to treat multiple sclerosis (MS), which the team hopes will target the root causes of schizophrenia in a far more fundamental way than current therapies.

The trial builds on more than a decade’s work by Oliver Howes, a professor of molecular psychiatry at the MRC London Institute of Medical Sciences and a consultant psychiatrist at the Maudsley Hospital in south London. Howes’s team is one of several worldwide to have uncovered evidence that abnormalities in immune activity in the brain may lie at the heart of the illness – for some patients, at least.

“In the past, we’ve always thought of the mind and the body being separate, but it’s just not like that,” said Howes. “The mind and body interact constantly and the immune system is no different. It’s about changing the way we think about mental illnesses.”

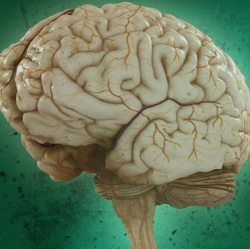

Recent work by Howes and colleagues found that in the earliest stages of schizophrenia, people experience a surge in the number and activity of immune cells in the brain. As well as fighting infection, these cells, called microglia, have a “gardening” role, pruning unwanted connections between neurons. But in schizophrenia patients, the pruning appears to become more aggressive, leading to vital connections being lost.

“We studied people in that [initial] phase of the illness and saw microglial changes,” said Howes. “It shows that it’s something [happening] very early on and seems to be driving the illness.”

The most extensive pruning appears to occur in the frontal cortex, the brain’s master control centre, and also the auditory regions, which could explain why patients often hear voices. The frontal cortex indirectly controls the brain’s levels of dopamine – a surge in this brain chemical is thought to explain the delusions and paranoia experienced by those with schizophrenia.

Nearly all existing medications work by blocking dopamine, which can bring psychotic symptoms under control, but fail to protect the brain’s basic architecture from damage.

“The current drugs are based on 1950s technology; they all still work in exactly the same way,” said Howes. “They are only able to target the delusion side of things. It’s like getting a sledgehammer and squashing it down.”

There is a growing appreciation that other, perhaps less well-known, symptoms associated with schizophrenia – memory and cognitive problems, and lack of motivation – can have an equally profound impact on patients, and existing drugs do little to help this side of the disease. “It’s typically [these other] symptoms that are the most disabling,” said Toby Pillinger, a psychiatrist and King’s College London researcher involved in the study.

The latest trial, a collaboration between MRC scientists and King’s College London, involves treating patients with a monoclonal antibody drug, called Natalizumab, that is already licensed for MS. In MS, the brain’s immune cells go awry by attacking a different aspect of the brain’s wiring. And although the diseases manifest in very different ways, apparent parallels in the underlying biology raise the possibility that the MS drug might help schizophrenia patients.

The drug works by targeting microglia and restricting their movement around the brain, which scientists hope could prevent the over-pruning of vital connections. In doing so, it could potentially address the disease’s full spectrum of symptoms.