Using brain scans combined with a personal history of any early life trauma, such as abuse or neglect, researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine successfully predicted with 80 percent accuracy whether antidepressants would help patients recover from depression.

“We think our results are especially strong because we demonstrated that accuracy is robust by confirming it with cross-validation techniques,” said Leanne Williams, PhD, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences.

A paper describing the findings was published online Oct. 10 in the Proceedings of the National Academies of Science. Williams is the senior author. Postdoctoral scholar Andrea Goldstein-Piekarski, PhD, is the lead author.

“Currently, finding the right antidepressant treatment is a trial-and-error process because we don’t have precise tests,” Williams said. “For some people this process can take years. As a result, depression is now the leading cause of disability.”

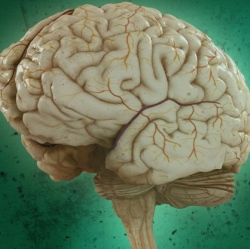

For the trial, the researchers conducted brain scans on 80 participants with depression. Participants lay in a functional MRI machine while viewing images of happy faces and fearful faces on a screen in front of them. Each face triggered brain circuits involving the amygdala, an almond-shaped structure linked to the experiencing of emotions.

The scans were conducted both before and after an eight-week treatment period with three commonly used antidepressants: sertraline (Zoloft), escitalopram (Lexapro) and venlafaxine (Effexor). Participants also completed a 19-item questionnaire on early life stress, which assessed exposure to abuse, neglect, family conflict, illness or death (or both), and natural disasters prior to the age of 18.

The researchers analyzed the pretreatment imaging and the questionnaire to predict how the individual patients would respond immediately after the eighth week. “Our predictions were correct,” Goldstein-Piekarski said.

Using a statistical analysis called predictive modeling, study results showed that participants exposed to a high level of childhood trauma were most likely to recover with antidepressants if the amygdala was reactive to the happy faces. Those with a high level of childhood trauma whose amygdala showed low reactivity to the happy faces were less likely to recover with antidepressants.

“We were able to show how we can use an understanding of the whole person, their experiences and their brain function and the interaction between the two, to help tailor treatment choices,” Williams said. “We can now predict who is likely to recover on antidepressants in a way that takes into account their life history.”