A 44-year-old British man may have become the first person in the world to be cured of HIV. Tests showed the virus had become undetectable in the blood of the previously HIV-positive man, after he was treated with a pioneering new therapy designed to eradicate the virus.

Researchers have cautioned that it is too early to tell if the treatment has really worked but said the man, a social worker, had made "remarkable progress".

The patient was the first of 50 people to complete a trial of the ambitious treatment which launches a two-stage “kick and kill” attack on the virus.

The new therapy is unique in that it tracks down and destroy HIV in every part of the body, including in the dormant cells that evade current treatments.

“This is one of the first serious attempts at a full cure for HIV,” Mark Samuels of Britain’s National Institute for Health Research told The Sunday Times.

”This is a huge challenge and it’s still early days, but the progress has been remarkable," he said.

The clinical trials, which are being paid for by the NHS, are the result of a collaboration between doctors and scientists at the universities of Oxford, Cambridge, Imperial College London, University College London and King’s College London.

The man, who has not been named, said he participated in the trial to help others with the disease.

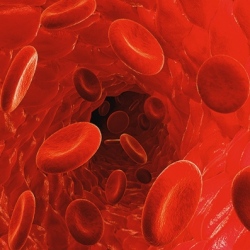

HIV, which stands for ”human immunodeficiency virus,“ is mainly transmitted through sexual acts or by using infected needles. The virus weakens a person’s immune system by destroying T-cells which are crucial to fighting disease and infection.

About 36.7 million people are living with HIV worldwide, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Antiretroviral therapies target and suppress active infected cells but they leave millions of dormant infected T-cells lying in wait throughout the body. This means existing treatments can effectively control HIV but do not cure the disease.

The new treatment, however, would both suppress infections and kill the reservoir of dormant cells, The Sunday Times reported.

Sarah Fidler, a consultant physician and professor at Imperial College London, said medical tests of the potentially breakthrough therapy would continue for the next five years.

”It has worked in the laboratory and there is good evidence it will work in humans too,“ Ms Fidler said. ”But we must stress that we are still a long way from any actual therapy."