New UCLA research indicates that lost memories can be restored, offering hope for patients in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. For decades, most neuroscientists have believed that memories are stored at the synapses, the connections between brain cells, or neurons, which are destroyed by Alzheimer’s disease.

The new study provides evidence contradicting the idea that long-term memory is stored at synapses. “Long-term memory is not stored at the synapse,” said David Glanzman, a senior author of the study, and a UCLA professor of integrative biology and physiology and of neurobiology. “The nervous system appears to be able to regenerate lost synaptic connections. If you can restore the synaptic connections, the memory will come back. It won’t be easy, but I believe it’s possible.”

Glanzman’s research team studies a type of marine snail called Aplysia to understand the animal’s learning and memory. The Aplysia displays a defensive response to protect its gill from potential harm, and the researchers are especially interested in its withdrawal reflex and the sensory and motor neurons that produce it.

They enhanced the snail’s withdrawal reflex by giving it several mild electrical shocks on its tail. The enhancement lasts for days after a series of electrical shocks, which indicates the snail’s long-term memory. Glanzman explained that the shock causes the hormone serotonin to be released in the snail’s central nervous system.

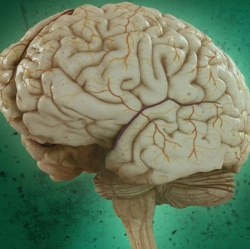

Long-term memory is a function of the growth of new synaptic connections caused by the serotonin, said Glanzman, a member of UCLA’s Brain Research Institute. As long-term memories are formed, the brain creates new proteins that are involved in making new synapses. If that process is disrupted, for example by a concussion or other injury,the proteins may not be synthesized and long-term memories cannot form. (This is why people cannot remember what happened moments before a concussion.)