There’s an incredible amount we don’t understand about the workings of the human body and brain, and consciousness itself remains one of the great mysteries of science. Which is weird, because in some senses it’s about the only thing we can be sure exists. It doesn’t matter whether life is a simulation, or even whether you really exist, I know that I’m having a subjective experience, and that may be the only truth each of us can be sure of.

The fact that this subjective experience can be switched off, whether by dropping into a deep sleep, getting knocked out or going under anesthesia, does nothing but add to the weirdness of it all. Things are happening to and around you, your awareness is just not online. The fact that there are highly paid and highly trained anesthetists who put people to sleep for a living merely reflects decades of trial and error, rather than a complete understanding of how an anesthetic drug works. Now, researchers from the University of Wisconsin, Madison, appear to have made a bit of a breakthrough.

In a study published in the journal Neuron, the team showed that at a frequency of 50 Hz, electrical stimulation of the central lateral thalamus, a region once thought of mainly as a relay, amplification and processing station, was able to pull macaque monkeys out of an anesthetized state and elicit normal waking behaviors.

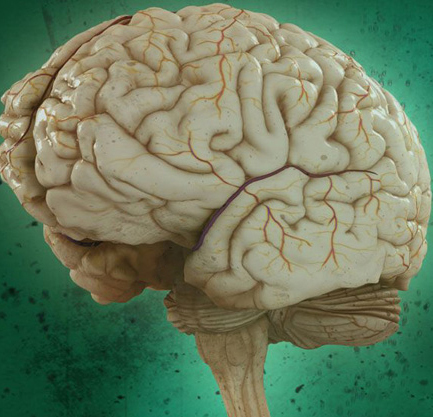

Scientists have long been studying the thalamus, which sits deep in the brain near the brain stem, to learn what role it plays in sleep, waking, consciousness and alertness. But this research, in which targeted electrical stimulation was applied to a specific area, narrowed the search down further than ever before. The electrodes used in the study were more tailored to the shape of the brain structures they were designed to work on, and the electrical stimulation was designed to mimic the activity of a normal, waking brain.

“We found that when we stimulated this tiny little brain area, we could wake the animals up and reinstate all the neural activity that you’d normally see in the cortex during wakefulness,” says senior author and assistant professor Yuri Saalmann. “They acted just as they would if they were awake. When we switched off the stimulation, the animals went straight back to being unconscious.”

The researchers hope this discovery might be able to help people with “disorders of consciousness” – for example, it might be possible to bring people out of comas with consciousness-starting devices, or give narcolepsy sufferers the ability to self-stimulate when they’re falling asleep at an inopportune time.