Nearly 4,000 people in the US are waiting for heart transplants. And on average, it takes about six months to get one, during which time some patients will die. So researchers have been trying for decades to make an artificial heart that can be permanently implanted.

But building one that imitates a real heart over a long period of time without breaking or causing infections or blood clots is incredibly difficult. One problem is that the more parts there are, the more things could go wrong. To solve the problem, Sanjiv Kaul and his team at Oregon Health and Science University are developing an artificial heart with an extremely simple design, it contains a single moving piece with no valves. They believe it could be the first such device that could last the rest of a person’s life.

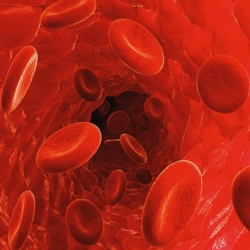

Originally designed by Richard Wampler, OHSU’s artificial heart creates a blood flow that mimics a natural pulse. It replaces the human heart’s two lower chambers, the ventricles, with a titanium tube containing a hollow rod that moves back and forth. This back-and-forth motion pushes blood to the lungs so it can extract oxygen and then move the oxygenated blood through the rest of the body.

Kaul hopes the simple design will overcome the limitations of previous artificial hearts. The first artificial heart, AbioCor, got limited approval from the US Food and Drug Administration in 2006. It was implanted in just 15 people and is no longer available. About the size of a grapefruit, it was too large to fit in children and many women.

Only one artificial heart, made by SynCardia, is currently available in the US. It’s meant to be a temporary fix while patients wait for a heart transplant. It requires people to carry around an external air compressor in a backpack that pumps the implanted artificial heart from the outside.

Kaul thinks the device could be available to patients in five years or even perhaps even sooner. OHSU’s artificial heart will probably need to be charged with a small, hand-held battery pack outside the body. But the hope is that a smaller, more efficient battery could eventually be implanted under the skin and be recharged from the outside.