For five decades, Moore’s law held up pretty well: Roughly every two years, the number of transistors one could fit on a chip doubled, all while costs steadily declined. Today, however, transistors and other electronic components are so small they’re beginning to bump up against fundamental physical limits on their size.

Moore’s law has reached its end, and it’s going to take something different to meet the need for computing that is ever faster, cheaper and more efficient.

As it happens, Kwabena Boahen, a professor of bioengineering and of electrical engineering, has a pretty good idea what that something more is: brain-like, or neuromorphic, computers that are vastly more efficient than the conventional digital computers we’ve grown accustomed to.

This is not a vision of the future, Boahen said. As he lays out in the latest issue of Computing in Science and Engineering, the future is now.

"We’ve gotten to the point where we need to do something different," said Boahen, who is also a member of Stanford Bio-X and the Stanford Neurosciences Institute. "Our lab’s three decades of experience has put us in a position where we can do something different, something competitive."

30 years in the making

It’s a moment Boahen has been working toward his entire adult life, and then some. He first got interested in computers as a teenager growing up in Ghana. But the more he learned, the more traditional computers looked like a giant, inelegant mess of memory chips and processors connected by weirdly complicated wiring.

Both the need for something new and the first ideas for what that would look like crystalized in the mid-1980s. Even then, Boahen said, some researchers could see the end of Moore’s law on the horizon. As transistors continued to shrink, they would bump up against fundamental physical limits on their size. Eventually, they’d get so small that only a single lane of electron traffic could get through under the best circumstances.

What had once been electron superfreeways would soon be tiny mountain roads, and while that meant engineers could fit more components on a chip, those chips would become more and more unreliable.

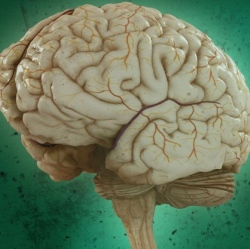

At around the same time, Boahen and others came to understand that the brain had enormous computing power – orders of magnitude more than what people have built, even today – even though it used vastly less energy and remarkably unreliable components, neurons.

How does the brain do it?

While others have built brain-inspired computers, Boahen said, he and his collaborators have developed a five-point prospectus – manifesto might be the better word – for how to build neuromorphic computers that directly mimic in silicon what the brain does in flesh and blood.

The first two points of the prospectus concern neurons themselves, which unlike computers operate in a mix of digital and analog mode. In their digital mode, neurons send discrete, all-or-nothing signals in the form of electrical spikes, akin to the ones and zeros of digital computers. But they process incoming signals by adding them all up and firing only once a threshold is reached – more akin to a dial than a switch.

That observation led Boahen to try using transistors in a mixed digital-analog mode. Doing so, it turns out, makes chips both more energy efficient and more robust when the components do fail, as about 4 percent of the smallest transistors are expected to do.

From there, Boahen builds on neurons’ hierarchical organization, distributed computation and feedback loops to create a vision of an even more energy efficient, powerful and robust neuromorphic computer.

The future of the future

But it’s not just a vision. Over the last 30 years, Boahen’s lab has actually implemented most of their ideas in physical devices, including Neurogrid, one of the first truly neuromorphic computers. In another two or three years, Boahen said, he expects they will have designed and built computers implementing all of the prospectus’s five points.

Don’t expect those computers to show up in your laptop anytime soon, however. Indeed, that’s not really the point – most personal computers operate nowhere near the limits on conventional chips. Neuromorphic computers would be most useful in embedded systems that have extremely tight energy requirements, such as very low-power neural implants or on-board computers in autonomous drones.

"It’s complementary," Boahen said. "It’s not going to replace current computers."

The other challenge: getting others, especially chip manufacturers, on board. Boahen is not the only one thinking about what to do about the end of Moore’s law or looking to the brain for ideas. IBM’s TrueNorth, for example, takes cues from neural networks to produce a radically more efficient computer architecture. On the other hand, it remains fully digital, and, Boahen said, 20 times less efficient than Neurogrid would be had it been built with TrueNorth’s 28-nanometer transistors.