Approximately 89,000 people die every year from melioidosis, an infection spread through bacteria from contaminated water and soil that can travel to the brain and spinal cord in less than 24 hours. A new study from Griffith University in Queensland, Australia discovered for the first time how the bacteria is contracted.

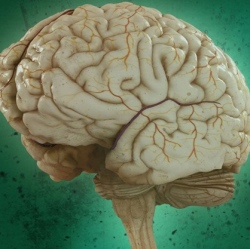

The finding could explain how other infectious bacteria make their way to the brain and spinal cord. The study, published in the journal Infection and Immunity on Tuesday, revealed the startling discovery that the bacteria Burkholderia pseudomallei enters through the nasal passage and uses the nerves in the nasal cavity as a pathway to the body’s central nervous system. Researchers used mice in their study to observe the bacteria’s pathway.

The bacteria travels through a crucial nerve connected to the nasal cavity and the brain stem called the trigeminal nerve, the largest of the 12 cranial nerves that supply feelings to the face and work as the motor nerve for functions such as chewing.

Researchers were able to rule out the bloodstream as a possible passageway for the bacteria by using a "capsule-deficient mutant of B. pseudomallei, which does not survive in the blood," according to the study.

The US Centers for Disease Control says that cases of melioidosis have been reported all over the world, but generally come from tropical and subtropical locations associated with periods of heavy rainfall. The regions with the most reported cases include Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore and Northern Australia.

Melioidosis has a 20 percent mortality rate in Australia and a 40 percent mortality rare in Southeast Asia. Doctors have a hard time diagnosing the disease before it reaches the brain stem because patients who contract the bacteria may not know they have it once they’ve been infected.

"You could have it and don’t know it, that’s scary," says Dr. James St. John, the head of Griffith University’s Clem Jones Centre for Neurobiology and Stem Cell Research. "It could just be sitting there waiting for an opportune moment, or it could just be doing small incremental damage over a lifetime. You could lose the function in your brain incrementally."

Further study is needed to determine the full extent of the damage that the bacteria causes to the central nervous system and if other more common bacteria such as staphylococcus and acne also move to the spinal cord following infection. It could even provide new insights into the root causes of more serious diseases such as Alzheimer’s.

A study published last May in the journal Translational Medicine by researchers at Harvard University theorized that the brain’s natural defense for fighting off viruses, fungi or bacteria could be the cause of the plaque that leave pockmarks on the brain over time.