For the three to five percent of the general population with primary or chronic insomnia, the problem of having difficulty falling asleep persists for a month or more, for no clear reason. Having insomnia for that long can make you feel sleepy and irritable during the day and cause memory problems or even anxiety and mood disorders.

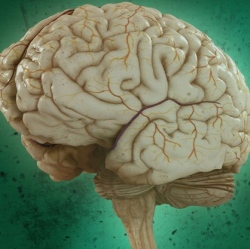

Past studies have suggested that the brains of insomnia patients are structured differently than people who sleep normally, suggesting that maybe the parts of the insomniac’s brain aren’t communicating well. Now a team of Chinese researchers used a special imaging technique to determine that people with insomnia have variations in their amount of white matter, which links different parts of the brain together. They published their study recently in the journal Radiology and the story was first reported by PsyPost

For a long time, the role of white matter wasn’t obvious, but in recent years scientists have learned that the connections it provides between disparate parts of the brain are essential for the brain to function properly. A loss of white matter can set the stage for stroke and dementia. But in the past, imaging techniques weren’t sophisticated enough to look at the amount and structure of white matter in particular.

In this study, the researchers used an imaging technique called diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging, which uses the tiny movements of water molecules to create detailed images that show the structures of tissues. They compared the images of the brains of 23 people who had chronic insomnia based on a self-assessment to those from 30 patients who did not.

They found that patients with insomnia had less white matter along certain pathways in the right hemisphere, which have been linked to regulating sleep and wakefulness. Pathways to and from the thalamus seemed particularly affected, which was not surprising, since the thalamus is critical to relay signals of sleep. But they also saw less white matter along tracts associated with cognitive, emotional, and sensorimotor function.

Today, people with insomnia can change their sleep habits, go to therapy, or take pills to sleep better. And the researchers aren’t quite sure how their findings will improve treatment. But the study does illuminate the connections between insomnia and other functions of the brain, which might help researchers find ways to reduce or eliminate symptoms in the future.