A chemical called resveratrol has come under renewed interest in the cause against Alzheimer’s. A study suggests that the chemical in red wine can slow the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. But how conclusive is the data, and does this mean we should all drink more wine? New Scientist looks at the evidence.

What is resveratrol?

Found in grapes, red wine and dark chocolate, many claims have been made about resveratrol. It has been touted as a potential panacea for a range of age-related disorders, including cancer, diabetes and neurological problems, but so far most of the data supporting these claims has come from lab studies and work in animals. There have been only a few, small studies in humans.

How might resveratrol protect us from age-related illness?

Extremely calorie-restricted diets greatly reduce age-related diseases in lab animals. This is thought to happen through the activation of a group of enzymes called sirtuins, which seem to affect gene expression and protect against the effects of stress, including a poor diet.

The hope is that resveratrol activates sirtuins to get the same benefits – like preventing the onset of age-related diseases, including Alzheimer’s – without having to stick to such a low-energy diet. But some experiments have suggested slowed ageing from caloric restriction may not be down to sirtuins after all.

What does the latest study show?

To see if resveratrol could delay the progression of Alzheimer’s disease in people , Scott Turner at Georgetown University Medical Centre in Washington DC and his team gave 119 people with mild to moderate symptoms of the disease either a gram of synthesised resveratrol twice a day in pills for a year, or a placebo.

Over the course of the study, those in the placebo group showed typical signs of Alzheimer’s progressing, including a decline in the level of amyloid beta protein in their blood – thought to be a sign that this compound was being taken from their blood and deposited in their brains. Those taking resveratrol, however, showed little or no change in amyloid beta levels in their blood.

Did the resveratrol make any difference to brain function?

This study was designed to test the safety of taking large doses of resveratrol, rather than look at whether it works. As such, the study is too small to detect any meaningful effect that it might have had on brain function. But Turner says they did see a slight improvement in one measure of cognitive function, although this wasn’t statistically significant. A larger study may find a stronger result.

Is amyloid a good indicator of Alzheimer’s disease?

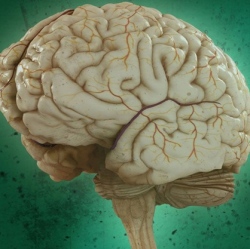

Alzheimer’s is typically characterised by the build-up of amyloid plaques in the brain, so it is often used as a biomarker for the disease. But questions remain over the role of amyloid in the disease – does it cause the condition or is it just a symptom? We won’t know how informative amyloid levels are until we find a successful way of stopping or slowing Alzheimer’s, says Neil Buckholtz of the NIH National Institute on Aging in Bethesda, Maryland, which funded this study.

Does this mean we should drink more wine?

“You can’t possibly consume enough resveratrol from food sources to reach the doses that were used in the study,” says James Hendrix, a scientist with the US charity Alzheimer’s Association. Turner estimates someone would have to drink 1000 bottles of red wine a day to even come close.

Natural supplements are problematic, too. Plants produce resveratrol in response to stress, such as a fungal infection, cold or drought, and the level of the compound in a plant can vary tremendously. The only way to guarantee the dose is with a synthesised product.

“Nature did not design resveratrol to treat Alzheimer’s disease, it designed it for some other reason that only a grape knows,” says Hendrix. But the molecule is a good starting point, he says. Chemists should be able to tweak the structure to make more of the chemical reach the brain and to reduce the dose and side effects.

Until then, it’s probably best to think of resveratrol and other dietary molecules as counteracting poor diet rather than preventing Alzheimer’s.