Scientists at a recently opened cancer institute at Cambridge University have begun work that is pinpointing changes in cells many years before they develop into tumours. The research should help design radically new ways to treat cancer, they say. The Early Cancer Institute – which has just received £11m from an anonymous donor – is focused on finding ways to tackle tumours before they produce symptoms. The research will exploit recent discoveries which have shown that many people develop precancerous conditions that lie in abeyance for long periods.

“The latency for a cancer to develop can go on for years, sometimes for a decade or two, before the condition abruptly manifests itself to patients,” said Prof Rebecca Fitzgerald, the institute’s director.

“Then doctors find they are struggling to treat a tumour which, by then, has spread through a patient’s body. We need a different approach, one that can detect a person at risk of cancer early on using tests that can be given to large numbers of people.”

One example of this is the cytosponge – a sponge on a string – which has been developed by Fitzgerald and her team. It is swallowed like a pill, expands in the stomach into a sponge and is then pulled up the gullet collecting oesophagus cells on the way. Those cells that contain a protein, called TFF3 – which is found only in precancerous cells – then provide an early warning that a patient is at risk of oesophageal cancer and needs to be monitored. Crucially, this test can be administered simply and on a wide scale.

This contrasts with current approaches to other cancers, added Fitzgerald. “At present, we are detecting many cancers late and are having to come up with medicines, which have become incrementally more expensive. We are often extending life by a few weeks at a cost of tens of thousands of pounds. We need to look at this from a different perspective.”

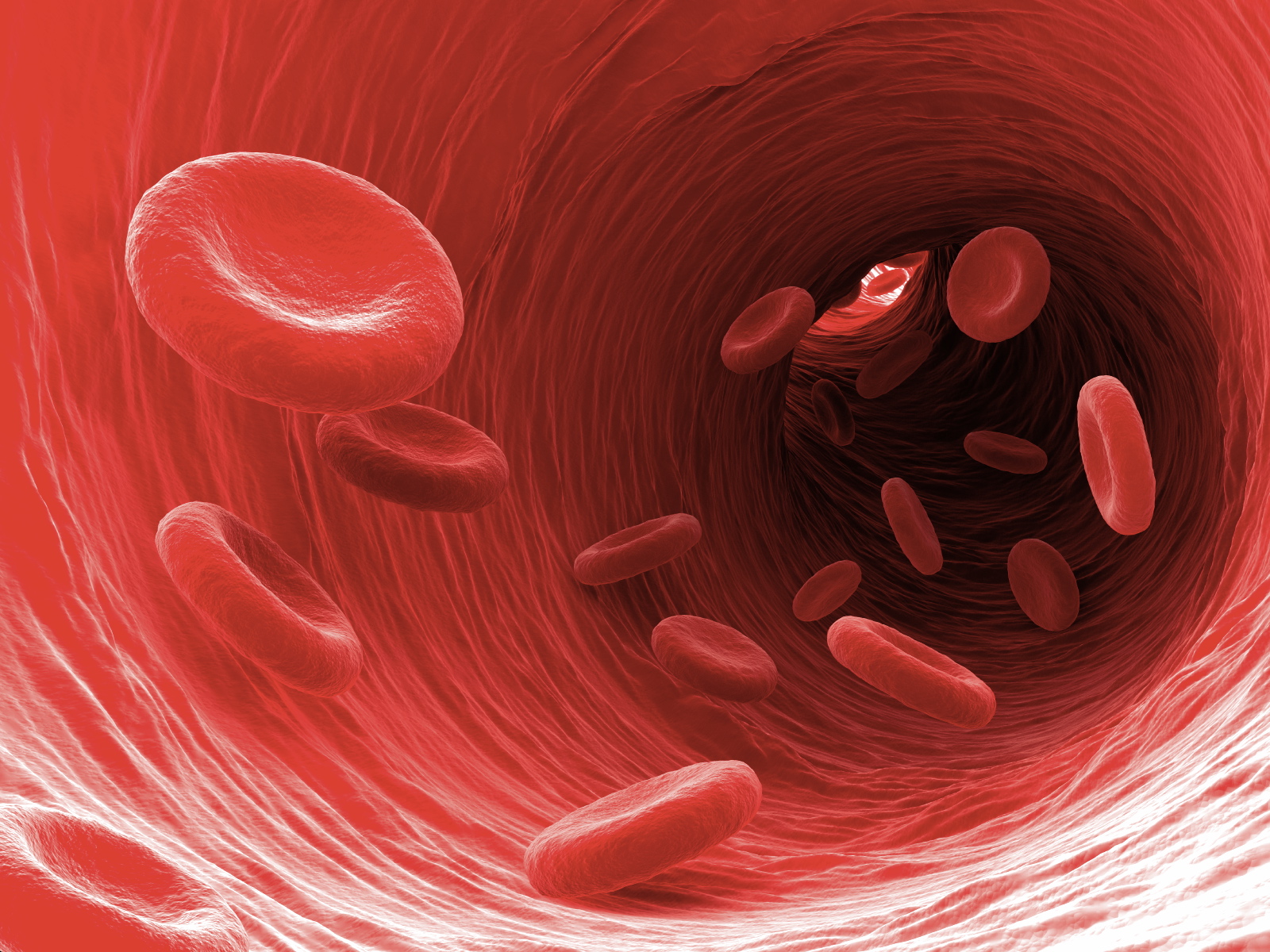

One approach being taken by the institute – which is to be renamed the Li Ka-shing Early Cancer Institute after the Hong Kong philanthropist who has supported other Cambridge cancer research – focuses on blood samples. Provided by women as part of past screening services for ovarian cancer and kept in special stores, these samples have now been repurposed by the institute. “We have around 200,000 such samples and they are a goldmine,” said Jamie Blundell, a research group leader at the institute.

Using these samples, researchers have identified changes that differentiate those donors who have subsequently been diagnosed with a blood cancer 10 or even 20 years after they provided samples, with those who did not develop such conditions.

“We are finding that there are clear genetic changes in a person’s blood more than a decade before they start to display symptoms of leukaemia,” said Blundell. “That shows there is a long window of opportunity that you could use to intervene and give treatments that will reduce the odds of going on to get cancer.”

Cancers grow in stages and by spotting those with cells that have taken an early step on this ladder, it should be possible to block or hamper further developments. The crucial point is that at this early stage there is time for doctors to take action and avoid them having to deal with a cancer at a late stage when it has spread.

A similar strategy is being taken by Harveer Dev, another group leader, who has investigated men who have had their prostates removed. His team are now developing biomarkers that will provide better ways to pinpoint those who are likely to suffer poor outcomes from prostate cancer, one of the most common tumours in the UK.

“Our pilot data suggests that these tests may be much better than existing PSA tests and will be crucial in spotting those who with prostate cancer that is likely to progress,” said Dev.

Pinpointing those at risk of cancer – for example, people from families who have an inherited predisposition to tumours – will form a key part of the institute’s strategy. In addition, it will focus on finding ways to reduce cancer risks, as well as ensuring treatments can be widely administered.

A woman had, in her 80s, decided to leave the university £1m for cancer research, Fitzgerald said. “However, she lived until she was over 100 and only died recently, so we only just got that donation. We want to understand what makes some live into very old age while others get cancer, so more people can live as long as she did.”