Seemingly countless self-help books and seminars tell you to tap into the right side of your brain to stimulate creativity. But forget the "right-brain" myth, a new study suggests it’s how well the two brain hemispheres communicate that sets highly creative people apart.

For the study, statisticians David Dunson of Duke University and Daniele Durante of the University of Padova analyzed the network of white matter connections among 68 separate brain regions in healthy college-age volunteers.

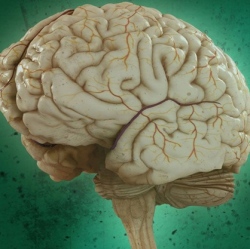

The brain’s white matter lies underneath the outer grey matter. It is composed of bundles of wires, or axons, which connect billions of neurons and carry electrical signals between them.

A team led by neuroscientist Rex Jung of the University of New Mexico collected the data using an MRI technique called diffusion tensor imaging, which allows researchers to peer through the skull of a living person and trace the paths of all the axons by following the movement of water along them. Computers then comb through each of the 1-gigabyte scans and convert them to three-dimensional maps, wiring diagrams of the brain.

Jung’s team used a combination of tests to assess creativity. Some were measures of a type of problem-solving called "divergent thinking," or the ability to come up with many answers to a question. They asked people to draw as many geometric designs as they could in five minutes. They also asked people to list as many new uses as they could for everyday objects, such as a brick or a paper clip. The participants also filled out a questionnaire about their achievements in ten areas, including the visual arts, music, creative writing, dance, cooking and science. The responses were used to calculate a composite creativity score for each person.

Dunson and Durante trained computers to sift through the data and identify differences in brain structure.

They found no statistical differences in connectivity within hemispheres, or between men and women. But when they compared people who scored in the top 15 percent on the creativity tests with those in the bottom 15 percent, high-scoring people had significantly more connections between the right and left hemispheres.

The differences were mainly in the brain’s frontal lobe.

Dunson said their approach could also be used to predict the probability that a person will be highly creative simply based on his or her brain network structure. "Maybe by scanning a person’s brain we could tell what they’re likely to be good at," Dunson said.

The study is part of a decade-old field, connectomics, which uses network science to understand the brain. Instead of focusing on specific brain regions in isolation, connectomics researchers use advanced brain imaging techniques to identify and map the rich, dense web of links between them.

Dunson and colleagues are now developing statistical methods to find out whether brain connectivity varies with I.Q., whose relationship to creativity is a subject of ongoing debate.

In collaboration with neurology professor Paul Thompson at the University of Southern California, they’re also using their methods for early detection of Alzheimer’s disease, to help distinguish it from normal aging.

By studying the patterns of interconnections in healthy and diseased brains, they and other researchers also hope to better understand dementia, epilepsy, schizophrenia and other neurological conditions such as traumatic brain injury or coma.

"Data sharing in neuroscience is increasingly more common as compared to only five years ago," said Joshua Vogelstein of Johns Hopkins University, who founded the Open Connectome Project and processed the raw data for the study.

Just making sense of the enormous datasets produced by brain imaging studies is a challenge, Dunson said.

Most statistical methods for analyzing brain network data focus on estimating properties of single brains, such as which regions serve as highly connected hubs. But each person’s brain is wired differently, and techniques for identifying similarities and differences in connectivity across individuals and between groups have lagged behind.

The study appears online and will be published in a forthcoming issue of the journal Bayesian Analysis.