NASA’s Curiosity rover has begun investigating one of the most interesting regions so far on its seven-year journey

NASA’s Curiosity rover has begun investigating one of the most interesting regions so far on its seven-year journey. Scientists call the area the “clay-bearing unit,” and sure enough, that name has turned out to be very apt. After drilling two new samples last month, the rover has finally confirmed high amounts of clay minerals, providing further proof that ancient Mars was once much wetter.

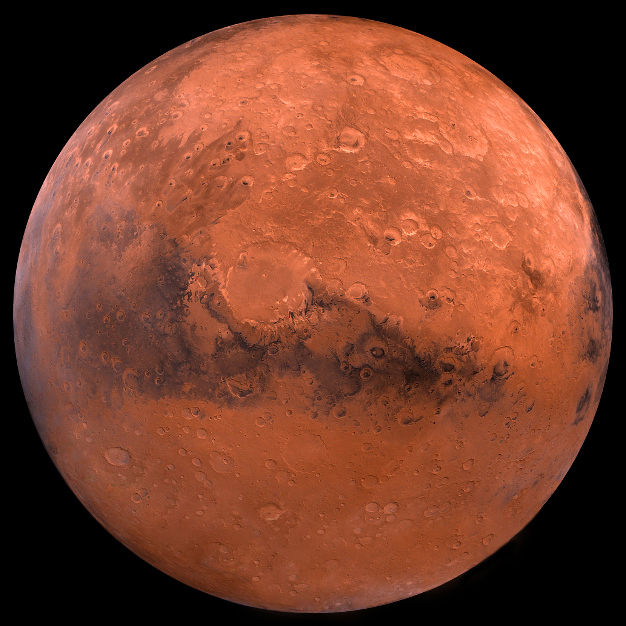

The presence of clay in the area was detected by the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) years before Curiosity ever touched down – in fact, it was one of the deciding factors in choosing a landing site. That’s because clay usually forms in water, adding to the growing body of evidence that Mars was once covered in rivers, lakes and even oceans. And where there was water, there could have been life.

Beginning on April 6, Curiosity drilled two samples (nicknamed Aberlady and Kilmarie) from the suspected clay-rich region, and immediately got some feedback that it had hit pay-dirt. The drill reportedly sliced through the soft material far more easily than it ever has before, making it the mission’s first sample to be obtained through only rotation of the drill bit.

And now, the rover has finished analyzing the two samples. While small amounts of clay have been detected in other places, these contained the highest amounts of clay minerals found on Mars so far. Also interesting is how different this dirt is from samples taken just a few kilometers away – the rover’s mineralogy instrument found very little hematite, an iron oxide mineral that was previously turning up in large amounts.

The science team says this latest finding backs up previous evidence that the area Curiosity has been exploring was home to an ancient lake. Since landing in 2012, the rover has found evidence of dried-up stream beds, organic molecules, water locked inside mineral compounds, and a layer-cake sediment structure.