Toronto and Baycrest Rotman Research Institute scientists have discovered a potential brain imaging predictor for dementia, which illustrates that changes to the brain’s structure may occur years prior to a diagnosis, before individuals notice their memory problems.

The joint study, published in the Neurobiology of Aging on May 8, looked at older adults who are living in the Toronto community without assistance and who were unaware of any major memory problems, but scored below the normal benchmark on a dementia screening test.

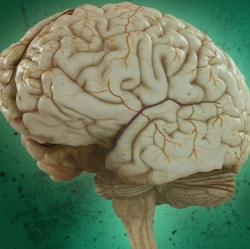

Within these older adults, researchers also found evidence of less brain tissue in the same subregion of the brain where Alzheimer’s disease originates (the anterolateral entorhinal cortex located in the brain’s temporal lobe).

This U of T-Baycrest study is the first to measure this particular brain subregion in older adults who do not have a dementia diagnosis or memory problems that affect their day-to-day routine. It is also the first study to demonstrate that performance on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) dementia screening test is linked to the volume (size) of this subregion, along with other brain regions affected early in the course of Alzheimer’s disease.

"This work is an important first step in determining a procedure to identify older adults living independently at home without memory complaints who are at risk for dementia," says Dr. Morgan Barense of U of T’s Department of Psychology and senior author on the study.

The team studied 40 adults between the ages of 59 and 81 who live independently (or with a spouse) at home. All participants were tested on the MoCA. Those scoring below 26 – a score that indicates a potential problem in memory and thinking skills and suggests further dementia screening is needed – were compared to those scoring 26 and above.

"The early detection of these at-risk individuals has the potential to facilitate drug developments or other therapeutic interventions for Alzheimer’s disease," says Dr. Rosanna Olsen, first author on the study, RRI scientist and assistant professor in U of T’s Department of Psychology. "This research also adds to our basic understanding of aging and the early mechanisms of Alzheimer’s disease." Scientists were able to reliably measure the volume of the anterolateral entorhinal cortex by using high-resolution brain scans that were collected for each participant.

The strongest volume differences were found in the exact regions of the brain in which Alzheimer’s disease originates. The researchers are planning a follow-up study to determine whether the individuals who demonstrated poor thinking and memory abilities and smaller brain volumes indeed go on to develop dementia.

"The MoCA is good at diagnosing mild cognitive impairment (MCI) (a condition that is likely to develop into Alzheimer’s) and we are seeing that it may identify MCI in people who are not aware of a decline in their memory and thinking skills," said Dr. Barense.

Alzheimer’s disease is a devastating neurodegenerative illness with widespread personal, societal and economic consequences. Currently, 564,000 Canadians currently live with dementia and 1.1 million Canadians are affected by the disease, according to the Alzheimer Society of Canada. There are 25,000 new cases of dementia diagnosed every year in Canada and it costs $10.4 billion to care for those living with dementia.

"A key take-away from the study is that it highlights the utility of the MoCA test in identifying individuals who are at-risk for dementia," said Dr. Olsen.