Pundits have been fretting a lot lately about robots leaving humans behind, taking our jobs and possibly a lot more, as in The Matrix and Terminator films. Christof Koch, my go-to source for brain science for 25 years, has proposed a solution. To keep up with machines, we should boost our cognitive powers with brain implants.

Koch, who directs the Allen Institute for Brain Science, which has an annual budget of more than $100 million, floats this idea in a Wall Street Journal essay, “To Keep Up With AI, We’ll Need High-Tech Brains.” The subhead: “Technologies that enhance the human brain will be essential to avoid a dystopian future fueled by the rise of artificial intelligence.”

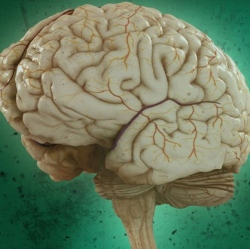

Koch looks at non-invasive methods, such as transcranial magnetic stimulation, but he doesn’t think those will be sufficient. “Ultimately, to boost our brain power, we need to directly listen to and control individual neurons: the atom of perception, action, memory and consciousness. And for that, we need to directly access brain tissue, requiring (for now) at least some surgery to penetrate the skull.”

Koch notes that brain implants are already helping paralyzed people control computers and robots, and they are being investigated as treatments for depression and other mental disorders. Future implants could help us download huge amounts of information instantly, he claims, so we can learn “novel skills and facts without even trying.” Like Neo “learning” how to fly a helicopter in The Matrix!

“Another exciting prospect,” Koch says, is “melding two or more brains into a single conscious mind by direct neuron-to-neuron links.” Like The Borg in Star Trek! Koch urges a “crash program to design safe, inexpensive, reliable and long-lasting devices and procedures for manipulating brain processes inside their protective shell."

Whoa. A few responses pop into my un-enhanced mind: First, brain-implant pioneers like Jose Delgado and Robert Heath, who were infamous for experimenting on a bull and a gay man, respectively, and whose work I just described on this site, would have loved Koch’s proposal. They’d say, Yeah, bring it on! If we had more moola for our research, you’d be living in a neuro-utopia by now!

Second: Koch neglects obvious questions raised by his sci-fi vision. It’s scary enough that bad guys can hack into our smart phones and laptops. What if they could hack into our brains? Implants would give Big Brother the ultimate form of mind-reading and mind-control.

Third, and this is my most important point: We are nowhere close to being able to enhance the brain in the manner that Koch envisions. Scientists have been experimenting with neuro-technologies for mental illness for more than half a century, and they have little to show for it.

Reliably integrating neural tissue and digital technologies would require cracking the neural code, the brain’s software, which transforms processes in the brain into perceptions, memories, emotions, decisions. It was Koch himself who made me doubt that science will solve the neural code any time soon, if ever.

As I pointed out in a column last year, neuroscientists have, if anything, too many candidates for a neural code. There are population codes, rate codes, temporal codes, grandmother-cell codes, chaotic codes and others. Koch once told me that the neural code is almost certainly not as “simple and as universal as the genetic code.”

Neural codes seem to vary in different species and even in different sensory modes within the same species. “The code for hearing is not the same as that for smelling,” Koch explained, ”in part because the phonemes that make up words change within a tiny fraction of a second, while smells wax and wane much more slowly.”

“There may be no universal principle” governing neural-information processing, Koch said, “above and beyond the insight that brains are amazingly adaptive and can extract every bit of information possible, inventing new codes as necessary.” So little is known about how the brain processes information that “it’s difficult to rule out any coding scheme at this time.”

Koch gave me this skeptical overview of neural-code research more than a dozen years ago. Since then there has been plenty of neuro-hype but no genuine breakthroughs in cracking the neural code. Koch has thrown his weight behind a mind-model called integrated information theory. It implies that even a single proton might be conscious, which means that consciousness pervades the entire cosmos, as decreed by the mystical doctrine panpsychism. Koch’s backing of integrated information theory seems to me like a sign of desperation.

So does his call for research aimed at turning us into super-intelligent cyborgs. Koch is perhaps seeking a grand justification for the Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) Initiative, a multi-billion-dollar federal program that supports research at the Allen Institute and elsewhere.

Koch is genuinely worried about humanity’s future. That was clear when I interviewed him last year in Seattle for a book I’m writing on the mind-body problem. He expressed concern over inequality, political instability, nuclear terrorism and war. He feared that science, far from solving our problems, might exacerbate them.

Advances in artificial intelligence, for example, could displace human transportation workers. “Vast numbers of trucks and cabs will be automated because it’s safer, cheaper and quicker,” Koch told me. “Well, what are we going to do with these 3.5 million [drivers]? Are we going to turn them into Java programmers? I doubt it. If we don’t look after them, they may get angry, and we will have more social discord.”

Artificial intelligence could wreak havoc in other ways. A stock-picking program might goad humans into war to boost the performance of defense-industry stocks. “It doesn’t want to take over the world,” Koch explained, “it just wants to maximize its return on investment. Law of unintended consequences, happens all the time.” Moreover, machines might eventually outsmart us. “It’s something to worry about,” Koch said.