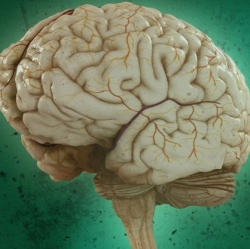

Electrical brain stimulation could benefit stroke patients by boosting the effects of rehabilitation therapy, new research suggests. Patients who were given electrical brain stimulation during a rehabilitation programme performed better on a range of tasks than those taking part in the rehabilitation programme.

“It is an exciting message because there is so much frustration about people not reaching their true recovery potential,” said Professor Heidi Johansen-Berg, an author of the study from the University of Oxford, highlighting the fact that the cost of programmes and limited availability of therapists often restricts the amount of rehabilitation offered to patients.

To probe the effects of brain stimulation, the researchers chose 24 patients who had experienced a stroke at least six months before, and who had difficulties with moving one hand. The participants were then split into two groups.

The first group underwent nine consecutive days of rehabilitation training, with each session lasting an hour. For the first 20 minutes, the patients had two electrodes placed on their heads and a direct current applied, a process known as anodal transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). This is stimulation is thought to prime the brain for learning.

The second group also underwent the nine-day programme, but while they too had electrodes placed on their head for the first 20 minutes, the current was turned off after the first 10 seconds, leading to a placebo trial.

The results indicate that brain stimulation bolstered the effect of the rehabilitation therapy, with patients who underwent the stimulation scoring appreciably higher on two of the tests – those related to carrying out particular tasks with the hand such as picking up a paper-clip – in assessments carried out three months after the therapy. For third test, which measured effects such as the strength of grip, brain stimulation was not linked to improvements.

The research also found that patients who underwent the brain stimulation had larger increases in activity in regions of the brain associated with movement than those who had been given the placebo treatment – an effect that was seen from fMRI scans taken immediately after the nine-day programme and one month later.

“What is particularly important about [the study] is that it does relate the functional improvements with the neuroimaging changes – and that is very encouraging,” said Burridge.

But Dr Nick Ward from University College London warns that the study is unlikely to lead to a change in treatment programmes any time soon. “I would call this a proof of principle study,” he said. “This is not something that you can translate into the NHS or any other clinical service immediately.”