Losing your sense of smell may mark the start of memory problems and possibly Alzheimer’s disease, a study suggests. Researchers found that adults who had the worst smell test scores were 2.2 times more likely to begin having mild memory problems. And if they already had these memory problems, they were more likely to progress to full-blown Alzheimer’s disease.

"The findings suggest that doing a smell test may help identify elderly, mentally normal people who are likely to progress to develop memory problems or, if they have these problems, to progress to Alzheimer’s dementia," Roberts said. "Physicians need to recognize that this may be a possible screening tool that can be used in the clinic," she added.

But Roberts also cautioned that the findings do not apply to people who have always had difficulty with smell because of chronic respiratory tract conditions. The report was published online Nov. 16 in JAMA Neurology.

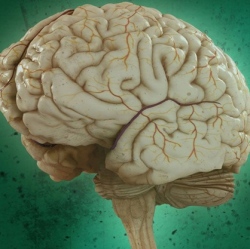

Roberts theorized that, as dementia begins and progresses, the parts of the brain that distinguish odors start to deteriorate. For the study, she and her and colleagues collected data on more than 1,400 mentally normal adults who were an average of 79 years old.

Over an average of 3.5 years of follow-up, 250 people developed memory problems (mild cognitive impairment). In addition, 64 among 221 people with the most serious memory problems developed dementia, the findings showed.

The smell test included six food-related and six nonfood-related scents (banana, chocolate, cinnamon, gasoline, lemon, onion, paint thinner, pineapple, rose, soap, smoke and turpentine), according to the study.

As the inability to identify smells increased, so did the likelihood of increasing memory problems and Alzheimer’s disease, Roberts said.

However, the association seen in the study did not prove a cause-and-effect relationship. And no link was found between a decreased sense of smell and other thinking problems associated with mild cognitive impairment, the researchers reported.

"These findings may indicate that there could be a problem linked to neurodegenerative diseases in general," said James Hendrix, the director of global science initiatives at the Alzheimer’s Association.

In the future, he added, a smell test could be an early indicator that something is going wrong with someone’s brain. "It would need follow-up to determine whether it was Alzheimer’s disease or Parkinson disease or some other condition," Hendrix said. But he noted that it’s too soon to start using a smell test as a diagnostic tool.

"Our ability to sense smell doesn’t just reside in our nose, there are receptors that are activated in our brains," he said. "We need to have a healthy brain to fully smell the world around us."