For people with a healthy immune system, cytomegalovirus (CMV) doesn’t present much of an issue. It’s transmitted through bodily fluids and, though it remains in the body for a person’s entire life, the immune system causes the virus to stay dormant and prevent it from causing harm.

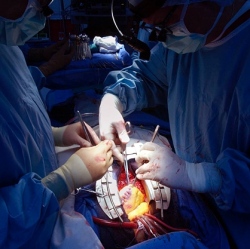

However, for people with a weakened immune system, such as people with a transplanted organ, CMV can cause an active infection.Now researchers from the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne in Switzerland have figured out a molecular switch for the virus, forcing it into dormancy when a person’s immune system isn’t able to do so on its own. The researchers published their findings this week in the journal eLife.

The researchers found a particular protein, called KAP1, was bound to the virus’ genetic code when it was dormant, but it wasn’t found when the virus was active. They theorized that this protein made the difference between the active and dormant viruses, so they sought out a way to control it. First, the researchers infected blood-producing stem cells with a latent form of the virus, then treated the cells with a common antimalarial drug called chloroquine. The chloroquine caused the protein to unbind itself, making the virus active again.

A better understanding of how the virus works means that researchers can develop a more standardized treatment for reactivating and killing the virus with antivirals before any tissue is transplanted to a new recipient. The researchers will continue to test this mechanism on the virus in bone marrow, then hopefully in human subjects.