Researchers describe how they tested the "protease-activated fluorescent probe for imaging cancer" at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, NC, in the journal Science Translational Medicine. The imaging technology, which uses an injectable blue liquid called LUM015.

The paper describes how the probe was able to identify cancerous tissue in live mice with sarcoma and in 15 patients undergoing surgery for soft-tissue sarcoma or breast cancer, without adverse effects.

Current imaging methods like MRI and CT scans do not always detect all the cancerous tissue at the margins of a tumor, so in the first operation some harmful cells can be left behind with the result that patients have to go back for more surgery or undergo radiation therapy.

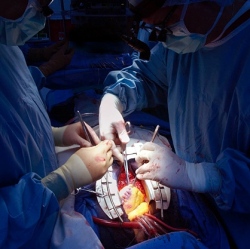

Co-senior author David Kirsch, a professor of radiation oncology and pharmacology and cancer biology at Duke, explains that while a pathologist can examine the tissue at the tumor margin under a microscope during surgery, because of the size of the affected area, it is not possible to look at all of it during the operation. He adds:

"The goal is to give surgeons a practical and quick technology that allows them to scan the tumor bed during surgery to look for any residual fluorescence."

The trial is the first to test a fluorescent probe that is protease-activated. The agent, LUMO15, fluoresces in the presence of cathepsin, a protease enzyme that is more common in cancer cells than healthy cells. The cancer cells use the enzyme to remodel their environment so the tumor can grow and spread.

When they tested the LUMO15 probe in mice, the researchers found the agent accumulated in tumors where it fluoresced on average five times more brightly than in regular muscle tissue.

The fluorescence is not visible to the naked eye – it has to be observed through a handheld imaging device that is also under development.