Roughly two years ago, the FDA made the historic decision to approve the first gene therapy in the US, finally realizing the therapeutic potential of hacking our biological base code after decades of cycles of hope and despair. Other approvals soon followed, including Luxturna to target inherited blindness and Zolgensma, a single injection that could save children with a degenerative disease from their muscles wasting away and dying before the age of two.

Yet despite their transformative potential, gene therapy has only targeted relatively rare—and often fatal—disorders. That’s about to change.

This year, a handful of companies deployed gene therapy against sickle-cell anemia, a condition that affects over 20 million people worldwide and 100,000 Americans. With over a dozen therapies in the run, sickle-cell disease could be the indication that allows gene therapy to enter the mainstream.

Yet because of its unique nature, sickle-cell could also be the indication that shines an unflinching spotlight on challenges to the nascent breakthrough, both ethically and technologically.

You see, sickle-cell anemia, while being one of the world’s best-known genetic diseases, and one of the best understood, also predominantly affects third-world countries and marginalized people of color in the US. So far, gene therapy has come with a hefty bill exceeding millions; few people afflicted by the condition can carry that amount. The potential treatments are enormously complex, further upping costs to include lengthy hospital stays, and increasing potential side effects. To muddy the waters even more, the disorder, though causing tremendous pain and risk of stroke, already has approved pharmaceutical treatments and isn’t necessarily considered “life-threatening.”

How we handle gene therapies for sickle-cell could inform many other similar therapies to come. With nearly 400 clinical trials in the making and two dozen nearing approval, there’s no doubt that hacking our genes will become one of the most transformative medical wonders of the new decade. The question is: will it ever be available for everyone in need?

Even those uninterested in biology have likely heard of the disorder. Sickle-cell anemia holds the crown as the first genetic disorder to be traced to its molecular roots nearly a hundred years ago.

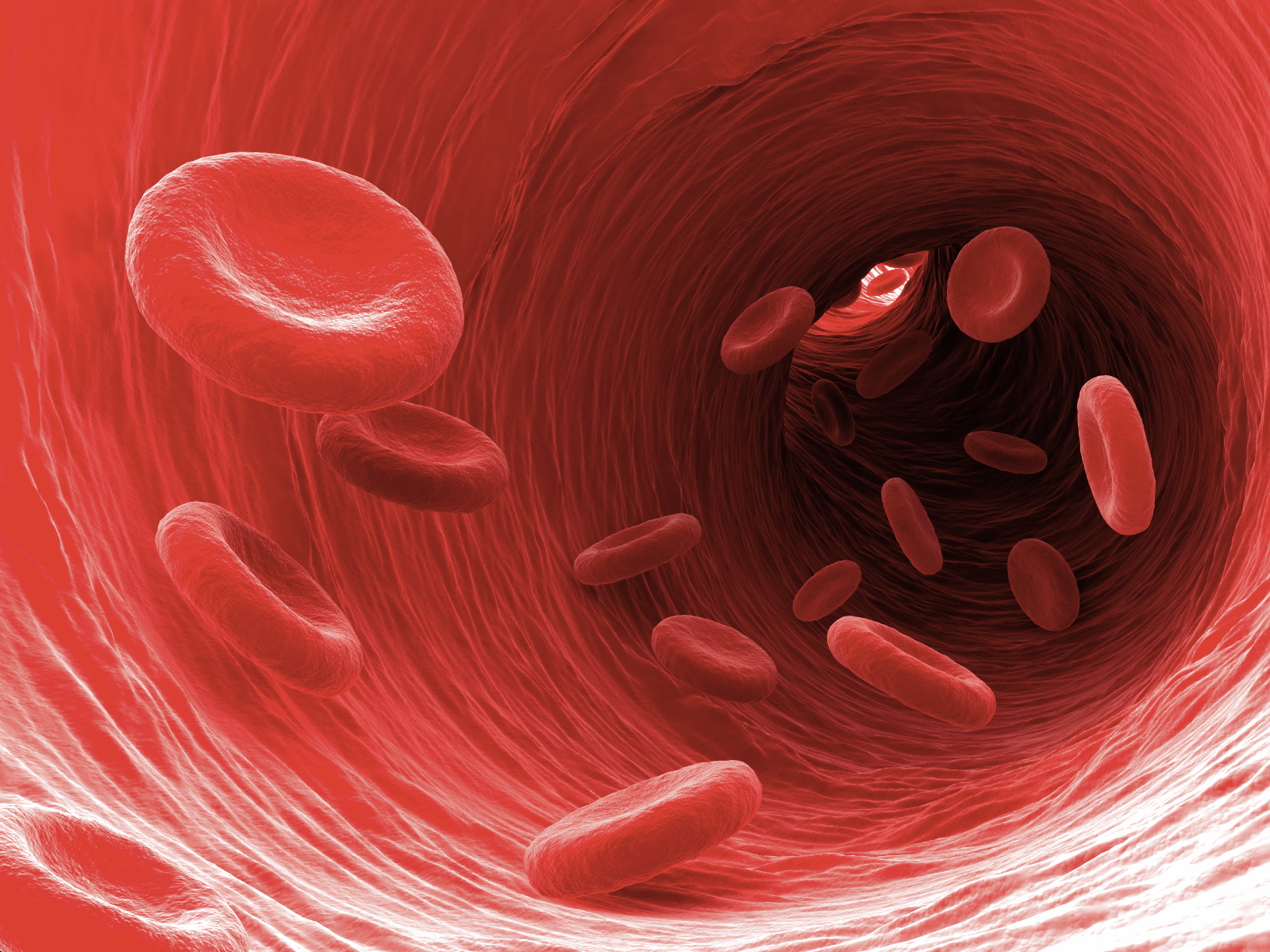

The root of the disorder is a single genetic mutation that drastically changes the structure of the oxygen-carrying protein, beta-globin, in red blood cells. The result is that the cells, rather than forming their usual slick disc-shape, turn into jagged, sickle-shaped daggers that damage blood vessels or block them altogether. The symptoms aren’t always uniform; rather, they come in “crisis episodes” during which the pain becomes nearly intolerable.

Kids with sickle-cell disorder usually die before the age of five; those who survive suffer a lifetime of debilitating pain and increased risk of stroke and infection. The symptoms can be managed to a degree with a cocktail of drugs—antibiotics, painkillers, and a drug that reduces crisis episodes but ups infection risks—and frequent blood transfusions or bone marrow transplants. More recently, the FDA approved a drug that helps prevent sickled-shaped cells from forming clumps in the vessels to further combat the disorder.

To Dr. David Williams at Boston Children’s Hospital in Massachusetts, the availability of these treatments—however inadequate—suggests that gene therapy remains too risky for sickle-cell disease. It’s “not an immediately lethal disease…it wouldn’t be ethical to treat those patients with a highly risky experimental approach,” he said to Nature.

Others disagree. Freeing patients from a lifetime of risks and pain seems worthy, regardless of the price tag. Inspired by recent FDA approvals, companies have jumped onto three different treatments in a bitter fight to be the first to win approval.

The complexity of sickle-cell disease also opens the door to competing ideas about how to best treat it.

The most direct approach, backed by Bluebird Bio in Cambridge, Massachusetts, uses a virus to insert a functional copy of the broken beta-globin gene into blood cells. This approach seems to be on track for winning the first FDA approval for the disorder.

The second idea is to add a beneficial oxygen-carrying protein, rather than fixing the broken one. Here, viruses carry gamma-globin, which is a variant mostly present in fetal blood cells, but shuts off production soon after birth. Gamma-globin acts as a “repellent” that prevents clotting, a main trigger for strokes and other dangerous vascular diseases.

Yet another idea also focuses on gamma-globin, the “good guy” oxygen-carrier. Here, rather than inserting genes to produce the protein, the key is to remove the breaks that halt its production after birth. Both Bluebird Bio and Sangamo Therapeutics, based in Richmond, California, are pursing this approach. The rise of CRISPR-oriented companies is especially giving the idea new promise, in which CRISPR can theoretically shut off the break without too many side effects.

But there are complications. All three approaches also tap into cell therapy: blood-producing cells are removed from the body through chemotherapy, genetically edited, and re-infused into the bone marrow to reconstruct the entire blood system.

It’s a risky, costly, and lengthy solution. Nevertheless, there have already been signs of success in the US. One person in a Bluebird Bio trial remained symptom-free for a year; another, using a CRISPR-based approach, hasn’t experienced a crisis in four months since leaving the hospital. For about a year, Bluebird Bio has monitored a dozen treated patients. So far, according to the company, none has reported episodes of severe pain.