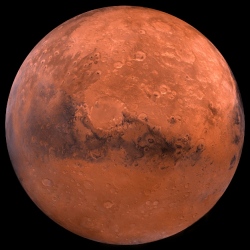

The important discovery comes after years of evidence of the Red Planet’s watery past and icy present, but this is the first time a significant amount of the life-giving liquid has been detected. Discovered through satellite radar readings, the lake lies beneath the ice caps at the south pole of Mars, and has profound implications for future missions and the search for life.

According to its discoverers, the lake lies below 1.5 km (0.9 mi) of solid ice, and stretches 20 km (12.4 mi) wide. Although temperatures at that spot plummet to about -68° C (-90° F), the water remains in a liquid form thanks to the heavy presence of sodium, magnesium and calcium salts. This, along with the immense pressure of the ice from above, lowers the freezing point.

The discovery was made by astronomers using the Mars Advanced Radar for Subsurface and Ionosphere Sounding (MARSIS) onboard the Mars Express orbiter. This instrument beams radar pulses down to the planet’s surface and measures how the waves reflect back to the spacecraft, which can tell scientists what kind of materials lie down there, even below the surface.

Using MARSIS to survey a region around the south pole of the Red Planet, the team collected 29 sets of radar samplings between May 2012 and December 2015. A section of this area returned very sharp changes in the radar signals, showing up as a bright spot in the image that’s consistent with a water interface. The radar profile, the researchers say, closely matches those of subglacial lakes here on Earth, beneath the ice sheets of Greenland and Antarctica.

Although it seems like "water found on Mars" headlines have been doing the rounds for years, this discovery is really what it’s all been building to. The majority of modern Mars is dry and barren, but plenty of evidence has been found that the Red Planet used to be a much wetter place. NASA studies suggest a vast ocean covered the planet’s northern hemisphere some 4.3 billion years ago, and lakes may have filled and emptied repeatedly over tens of millions of years in places like Gale Crater, the landing site of the Curiosity rover.

Nowadays, water exists on the Red Planet in the form of trace amounts of vapor in the atmosphere, or locked away in underground ice sheets and mineral compounds. Any liquid water was believed to be transitional, pooling in short-lived microscopic puddles or flowing down hillsides in the Martian summer.

The discovery of a large, stable reserve of liquid water on Mars is massive, giving us new potential targets for future missions and places to search for signs of past or present microbial life – although the sheer saltiness of it might kill those hopes.