Despite some exciting recent advances in early detection methods, autism spectrum disorder is still a frustratingly mysterious and elusive condition. Over 200 genes have been implicated in the condition, but no single mechanism has yet been identified to suggest possible treatment methods.

A new study is offering a clue into the origins of the disorder by finding a single dysfunctional protein may be responsible for coordinating expression in all the genes that result in autism susceptibility.

Great advances have been made in recent years, revealing a large assortment of genes that are potentially responsible for the varied behavioral and neurological traits associated with autism. But a genetic predisposition to developing autism is only part of the mystery. Environmental factors, particularly during pregnancy, are thought to play a large role in effecting the expression of those targeted genes.

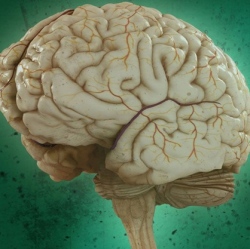

This new study, from an international team of researchers, has revealed that a single protein was found to be impaired in most cases of autism. This protein, called CPEB4, is vital in embryonic development, assisting with neuroplasticity and helping regulate the expression of certain genes during fetal brain development.

When the researchers studied the brains of a mouse model engineered to have disrupted CPEB4 activity, they found that most of the changes effected by the alteration happened to be in the same genes that previous research found to be implicated in autism. On top of this, the researchers found that the mice engineered with a CPEB4 imbalance were seen to display neuroanatomical, electrophysiological and behavioral phenotypes associated with autism.

"Since CPEB4 is known to regulate numerous genes during embryonic development, this protein emerges as a possible link between environmental factors that alter brain development and the genes that predispose to autism," says first author on the new research, Alberto Parras.

This isn’t the first interesting bit of research into the role of proteins in autism. A 2016 study from the University of Toronto zeroed in on a protein called nSR100 as potentially playing a major role in triggering autism-like behavior. That research found that not only was nSR100 seen in diminished volumes in human subjects with autism, but a mouse model engineered to have reduced nSR100 levels resulted in the animal displaying all the behavioral hallmarks of the condition.

The 2016 research was examining the action of a protein in the hope that it could be lightly modulated to help modify some of the negative behavioral symptoms associated with autism. However, this new research is much more concerned with the way a single protein can fundamentally alter the expression of hundreds of genes that regulate the growth of the brain in a prenatal environment.

Both studies are complementary insofar as they point to a more pragmatic future of autism treatments that target broader regulatory proteins instead of single genetic mutations.