There’s been plenty of research into how space travel affects the body.

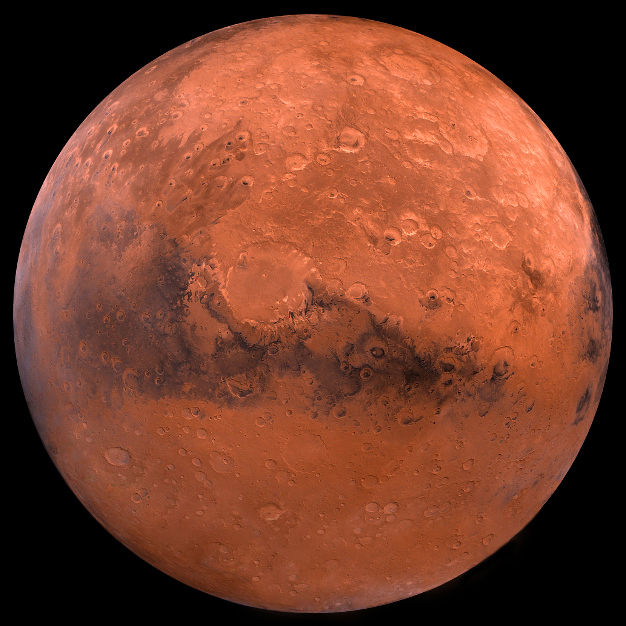

Now, in a study led by University College London, researchers have conducted a range of experiments and analyses, the largest to date, into how the kidneys respond to longer spaceflights, like the one that’ll get us to Mars.

“We know what has happened to astronauts on the relatively short space missions conducted so far, in terms of an increase in health issues such as kidney stones,” said Dr Keith Siew, a research fellow in renal medicine at UCL and the study’s lead and co-corresponding author.

The researchers looked at physiological, anatomical and biomolecular data from 20 study cohorts, including samples from over 40 LEO space missions undertaken by humans and mice – mostly to the International Space Station – and 12 space simulations involving rats and mice.

In seven simulations, mice were exposed to GCR doses equivalent to 1.5- and 2.5-year Mars missions, emulating deep space travel. Structurally, both human and rodent kidneys appeared to be ‘remodeled’ by exposure to space conditions.

Previous studies have shown that astronauts have an unusually high rate of kidney stone formation, which has been attributed to microgravity causing bone loss that leads to a build-up of calcium in the urine.

The present study indicated that space flight fundamentally altered how the kidney processed salts, which likely contributed to the formation of kidney stones.

“If we don’t develop new ways to protect the kidneys, I’d say that while an astronaut could make it to Mars, they might need dialysis on the way back,” Siew said.

This study represents the most comprehensive data to date on how up to 2.5 years of space travel affects the kidneys, which is relevant to any proposed trip to Mars.

“Our study highlights the fact that if you’re planning a space mission, kidneys really matter,” said Stephen B. Walsh, from the UCL Department of Renal Medicine and a co-corresponding author on the study.

“You can’t protect them from galactic radiation using shielding, but as we learn more about renal biology, it may be possible to develop technological or pharmaceutical measures to facilitate extended space travel.”

The study was funded by the UK Space Agency, the Wellcome Trust, St Peters Trust, and Kidney Research UK and published in Nature Communications.