People with higher levels of lithium in their drinking water appear to have a lower risk of developing dementia, say researchers in Denmark. Lithium is naturally found in tap water, although the amount varies. The findings, based on a study of 800,000 people, are not clear-cut. The highest levels cut risk, but moderate levels were worse than low ones.

Experts said it was an intriguing and encouraging study that hinted at a way of preventing the disease. The study, at the University of Copenhagen, looked at the medical records of 73,731 Danish people with dementia and 733,653 without the disease.

Tap water was then tested in 151 areas of the country.

The results, published in JAMA Psychiatry, showed moderate lithium levels (between 5.1 and 10 micrograms per litre) increased the risk of dementia by 22% compared with low levels (below five micrograms per litre).

However, those drinking water with the highest lithium levels (above 15 micrograms per litre) had a 17% reduction in risk. The researchers said: "This is the first study, to our knowledge, to investigate the association between lithium in drinking water and the incidence of dementia.

"Higher long-term lithium exposure from drinking water may be associated with a lower incidence of dementia."

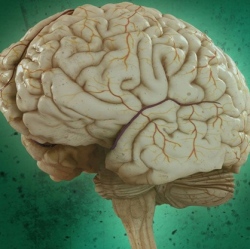

Lithium is known to have an effect on the brain and is used as a treatment in bipolar disorder. However, the lithium in tap water is at much lower levels than is used medicinally.

Experiments have shown the element alters a wide range of biological processes in the brain. This broad impact could explain the mixed pattern thrown up by the different doses, as only certain dosing sweet-spots change brain activity in a beneficial way.

Prof Simon Lovestone, from the department of psychiatry at the University of Oxford, said: "This is a really intriguing study.

"In neurons in a dish and in mouse and fruit-fly models of Alzheimer’s disease, lithium has been shown to be protective.

"Not only that, but lithium is used to treat people with bipolar disorder and some studies have suggested that people on lithium for this reason, often for life, might also be protected from Alzheimer’s."

He said there should now be studies to see if regular, small doses of lithium could prevent the onset of dementia.

At the moment, there is no drug that can stop, reverse or even slow the progression of the disease.

Dr David Reynolds, from the charity Alzheimer’s Research UK, said: "It is potentially exciting that low doses of a drug already available in the clinic could help limit the number of people who develop dementia.

"[Our analysis] suggests that a treatment that could delay dementia by just five years would mean that 666,000 fewer people develop dementia by 2050 [in the UK]."

The problem with this style of study – which looks for patterns in large amounts of data – is it cannot prove cause-and-effect.

Prof Tara Spires-Jones, from the Centre for Discovery Brain Sciences, at the University of Edinburgh, said: "This association does not necessarily mean that the lithium itself reduces dementia risk.

"There could be other environmental factors in the area that could be influencing dementia risk.

"Nonetheless, this is an interesting result that will prompt more research into whether lithium levels in the diet or drinking water may modify risk of dementia."