A team of NASA scientists may have resolved a mystery surrounding disappearing methane on Mars, that was detectable by NASA’s Curiosity rover but absent in readings taken by an orbiting ESA spacecraft. The tiny amounts of methane detected by the rover are of particular interest to planetary scientists searching for ET, as it may hint at the presence of life buried beneath the surface.

On our home world it is possible for methane to be created in a number of geological ways, but it is primarily emitted by animals of all shapes and sizes as a side effect of their digestive system. If methane were to be detected in another world’s atmosphere, it could be taken as a significant sign that there may be microbial life present in the alien soil.

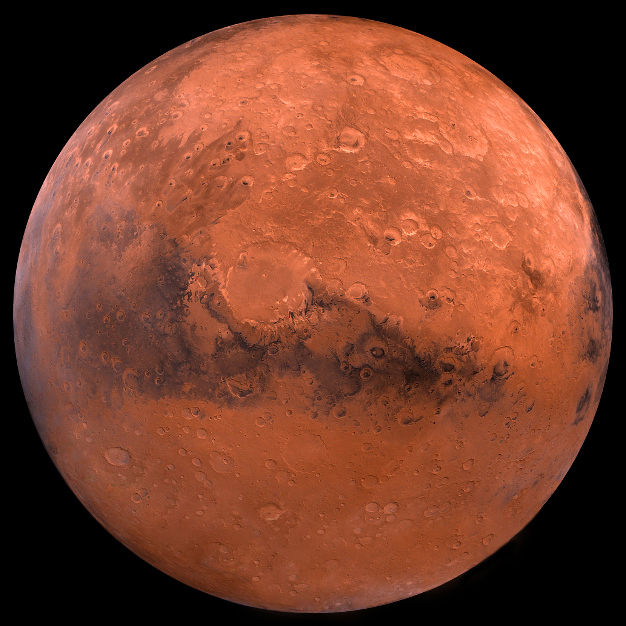

Back in 2004, NASA scientists announced that they had detected trace amounts of the gas in the Martian atmosphere, which naturally prompted a wave of excitement from the scientific community and members of the public alike.

Of course, it is still perfectly possible that the methane detected on the Red Planet is being created via a geological process, but it could equally be evidence of microbial life existing in the soil of a world that is not our own.

Namely, why are some instruments able to detect traces of methane while others, which theoretically should be capable of doing so, can’t?

Ordinarily, the TLS records around one half part of methane per billion in atmospheric volume, with occasional unexplained spikes of up to 20 parts per billion.

“When the Trace Gas Orbiter came on board in 2016, I was fully expecting the orbiter team to report that there’s a small amount of methane everywhere on Mars,” explained Chris Webster of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, lead scientist for the Tunable Laser Spectrometer instrument aboard the Curiosity rover.

“But when the European team announced that it saw no methane, I was definitely shocked.”

This made the discrepancy in the methane readings all the more baffling.

The team hypothesized that the methane was able to build up enough to be recorded by Curiosity because the atmosphere has been observed to be more placid during the Martian night time.

During the day, an increase in atmospheric vertical mixing could disperse the methane particles, and dilute them to the extent that there are too few to be detectable.

To test the theory, NASA instructed Curiosity to take methane readings starting during a Martian day, then again the next night, and finally once more the following day.

It was discovered that the nighttime methane readings corresponded closely to the average levels that had been detected since Curiosity had touched down on Mars.

During the day, the TLS was unable to detect any significant quantities of methane, corroborating the team’s theory. There are still overarching mysteries regarding the relative absence of methane from the Martian atmosphere.

Methane is thought to have a roughly 300-year lifespan, before its molecular bonds are destroyed by solar radiation. With a lifespan that long, the gas seeping from Gale Crater and other locations around Mars should have collected in large enough quantities in the Martian atmosphere as to be detected by ESA’s Trace Gas Orbiter.

This is not the case, and that fact suggests that there is a hitherto unknown process at work in the Martian atmosphere that is destroying the methane quickly, before it can collect.