Our bodies have developed a particularly unforgiving immune response when a threat is posed to our lungs. This is great for warding off illness, though is something of a double-edged sword regarding transplants, with the body often perceiving the incoming organ as a threat and seeking to destroy it.

But a new approach known as ex-vivo lung perfusion (EVLP) promises to boost the success rate of such procedures, by both repairing unhealthy donor lungs that wouldn’t otherwise make the grade and reducing the chances of rejection once it is implanted.

One of the main culprits behind the body’s aversion to new lungs are the donor’s white blood cells, known as leukocytes. Once the organ is implanted, these migrate into the recipient’s body where the immune system interprets them as dangerous and sets about attacking the organ, something known as acute rejection.

The current approach to countering this is immunosuppression, where the patient receives lifelong drug treatment to inhibit activity of the immune system. The problem is that this invites a whole other set of risks, such as heightened susceptibility to infections and cancer.

EVLP is an experimental technique that is currently being pursued by researchers around the world as a means of improving availability of lung transplantation therapy. It sees the donor’s lungs kept alive outside the body in a plastic dome for three to four hours, where they receive a supply of blood and nutrients. This can reverse injuries, remove excess lung water and ultimately make damaged lungs more suitable for transplantation.

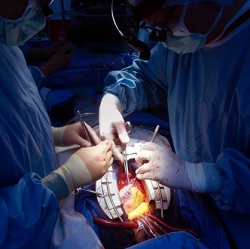

A team of researchers from the University of Manchester and Sweden’s University of Lund carried out a study involving the transplantation of pig’s lungs. Some were subjected to EVLP treatment, which in this case also involved the removal of leukocytes, while others where transplanted without the treatment as per normal. The recipients were then monitored for 24 hours.

The EVLP-treated lungs showed little signs of rejection, while the lungs transplanted without the treatment all showed signs of severe rejection. Because the lungs were only monitored for 24 hours, the scientists are not yet clear on the long term effects of the approach, but say that even delay in the onset of acute rejection would be advantageous in facilitating more successful transplants. They are also hopeful that the approach may complement new immunosuppressive drugs under development.

"Aside from the benefits shown in this study, it is possible that EVLP could be used to deliver drugs before the lung is implanted so that the patient’s immune system does not recognize the transplanted organ as harmful," says the University of Manchester’s Dr James Fildes, leader of the study. "EVLP opens up new possibilities in one of the most problematic areas of surgery."