What if curing cancer was as easy as getting an injection? That’s just what a pair of studies published this week tried to figure out. The two teams of researchers conducted independent Phase I trials of personalized vaccines designed to prime the patients’ immune systems against melanomas, a category of skin cancers.

In a scientific double whammy, both studies found that their vaccines, sometimes in combination with other immunotherapies, were able to prevent recurrence of the cancers in nearly all their subjects.

“We can safely and feasibly create a vaccine that is personalized to an individual’s tumor,” says Catherine Wu, senior author of one of the studies and associate professor at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston. “It’s not one-size-fits-all—rather, it’s tailored to the genetic composition of the patient’s tumor.”

Wu carried out her study with colleagues in Boston at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and the Broad Institute. The other study was conducted in parallel by researchers in Germany, led by study first author Ugur Sahin, the co-founder and CEO of BioNTech, a biotechnology company that focuses on personalized immunotherapy treatments.

Both studies targeted the same type of cancer: melanoma. These skin cancers (best known for their link to UV radiation from tanning) are a good first target, Wu says, because scientists have a good understanding of the mutations that cause them. These mutations are the key, says Mathias Vormehr, a co-author on Sahin’s study and a scientist at BioNTech.

"In principle, you can target any tumor that has mutations," Vormehr says. "And mutations are a main feature of tumors."

The goal of a cancer vaccine is to turn the patient’s own immune system against the cancer by teaching it to fight the tumor cells. This is similar to other vaccines like the flu vaccine which contains dead or weakened flu viruses that can’t actually do harm but can model what the the immune system should be prepared to fight.

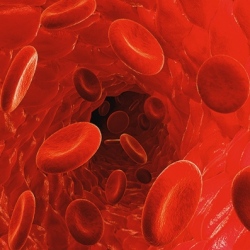

Past attempts to create cancer vaccines have used gene-carrying viruses to reprogram immune cells to recognize cancerous cells. Others removed some immune cells from the patient’s blood, taught them to recognize the cancer cells outside the body, then re-injected the trained immune cells into the patient to go to work.

The recent studies in Nature used neoantigen vaccines. Antigens are small proteins that decorate the outside of cells, and "neoantigens" refer to ones that are found only on cancer cells. Because they aren’t found on any healthy cells, neoantigens make a perfect target for the immune system, after all, you wouldn’t want the immune system to start attacking its own healthy cells. Normally, cancer cells evade the immune system by weakening its effects and by feigning the appearance of normal cells.

But, if the immune system learns to recognize the neoantigens delivered by the vaccine as harmful, it could then recognize and fight the cancer cells, too. Delivering mass amounts of neoantigens at once, which is what the vaccine would do, could trigger this recognition and the immune system might see neoantigens as harmful from then on.