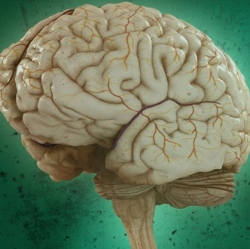

Imagine replacing a damaged eye with a window directly into the brain, one that communicates with the visual part of the cerebral cortex by reading from a million individual neurons and simultaneously stimulating 1,000 of them with single-cell accuracy, allowing someone to see again.

That’s the goal of a $21.6 million DARPA award to the University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley), one of six organizations funded by DARPA’s Neural Engineering System Design program announced this week to develop implantable, biocompatible neural interfaces that can compensate for visual or hearing deficits.*

The UCB researchers ultimately hope to build a device for use in humans. But the researchers’ goal during the four-year funding period is more modest: to create a prototype to read and write to the brains of model organisms, allowing for neural activity and behavior to be monitored and controlled simultaneously. These organisms include zebrafish larvae, which are transparent, and mice, via a transparent window in the skull.

The ability to talk to the brain has the incredible potential to help compensate for neurological damage caused by degenerative diseases or injury,” said project leader Ehud Isacoff, a UC Berkeley professor of molecular and cell biology and director of the Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute. “By encoding perceptions into the human cortex, you could allow the blind to see or the paralyzed to feel touch.”

How to read/write the brain

To communicate with the brain, the team will first insert a gene into neurons that makes fluorescent proteins, which flash when a cell fires an action potential. This will be accompanied by a second gene that makes a light-activated “optogenetic” protein, which stimulates neurons in response to a pulse of light.

To read, the team is developing a miniaturized “light field microscope.”** Mounted on a small window in the skull, it peers through the surface of the brain to visualize up to a million neurons at a time at different depths and monitor their activity.***

This microscope is based on the revolutionary “light field camera,” which captures light through an array of lenses and reconstructs images computationally in any focus.

The combined read-write function will eventually be used to directly encode perceptions into the human cortex, inputting a visual scene to enable a blind person to see. The goal is to eventually enable physicians to monitor and activate thousands to millions of individual human neurons using light.

Isacoff, who specializes in using optogenetics to study the brain’s architecture, can already successfully read from thousands of neurons in the brain of a larval zebrafish, using a large microscope that peers through the transparent skin of an immobilized fish, and simultaneously write to a similar number.

The team will also develop computational methods that identify the brain activity patterns associated with different sensory experiences, hoping to learn the rules well enough to generate “synthetic percepts”, meaning visual images representing things being touched, by a person with a missing hand, for example.

The brain team includes ten UC Berkeley faculty and researchers from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Argonne National Laboratory, and the University of Paris, Descartes.