Depression is like waking up to a rainy, dreary morning, every single day. Instead, every social interaction and memory is filtered through a negative lens. This aspect of depression, called negative affective bias, leads to sadness and rumination-where haunting thoughts tumble around endlessly in the brain.

In contrast, psychedelics rapidly trigger antidepressant effects with just one shot and last for months when administered in a controlled environment and combined with therapy.

Why? A new study suggests these drugs reduce negative affective bias by shaking up the brain networks that regulate emotion.

In rats with low mood, a dose of several psychedelics boosted their “Outlook on life.” Based on several behavioral tests, ketamine-a party drug known for its dissociative high-and the hallucinogen scopolamine shifted the rodents’ emotional state to neutral.

Rather than downers, these rats adopted a sunny mindset with an openness to further learning, replacing negative thoughts with positive ones. The study also gave insight into why psychedelics seem to work so fast.

Within a day, ketamine rewired brain circuits that shifted the emotional tone of memories, but not their content. The changes persisted long after the drugs left the body, possibly explaining why a single shot could have lasting antidepressant effects.

When treated with both high and low doses of the psychedelics, lower doses especially helped reverse negative cognitive bias-hinting it’s possible to lower psychedelic doses and still retain therapeutic effect. The results could “Explain why the effects of a single treatment in human patients can be long-lasting, days to months,” said lead author Emma Robinson in a press release.

Once maligned as hippie drugs, scientists and regulators are increasingly taking them seriously as potential mental health therapies for depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and anxiety.

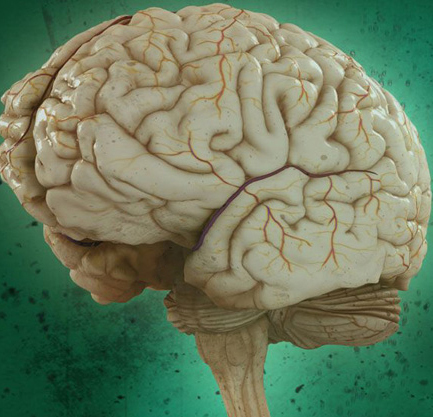

Often used as anesthesia for farm animals or as a party drug, ketamine caught the attention of neuroscientists for its intriguing action in the brain-especially the hippocampus, which supports memories and emotions. Our brain cells constantly reshuffle their connections.

Called “Neural plasticity,” changes in neural networks allow the brain to learn new things and encode memories. In depression, these channels erode, making it more difficult to rewire the brain when faced with new learning or environments.

The hippocampus also gives birth to new neurons in rodents and, arguably, in humans. Like adding transistors to a computer chip, these baby neurons reshape information processing in the brain. An earlier study in mice found the drug increases the birth of baby neurons to lower depression.

These studies in rodents, along with human clinical trials, propelled the US Food and Drug Administration to greenlight a version of the drug in 2019 for people with depression who have tried other antidepressant medications but didn’t respond to them.

While psilocybin and other mind-altering drugs are gaining steam as fast-acting antidepressants, we’re still in the dark on how they work in the brain. The new study followed ketamine’s journey and dug deeper by testing it and other hallucinogens in a furry little critter. Scientists can examine their neural networks before and after psychedelic treatments and hunt changes in their neural connections.

Rats treated with a low dose of psychedelics shifted their mood towards positivity, without notable side effects.