The NHS has announced it will attempt what is believed to be the first synthetic blood transfusion on human volunteers in 2017. If successful, such a medical breakthrough could help to create specialized donations for patients suffering from blood conditions and may even eventually give health services an unlimited supply of red blood cells.

Volunteers will be given only a few teaspoons of the synthetic blood to test for any adverse reactions. So far, lab tests have shown that the synthetic red blood cells are “comparable if not identical to the cells from a donor,” said Dr. Nick Watkins, assistant director of research and development at NHS Blood and Transplant, The Independent reported. The trials will first consist of transfusions made from the stem cells of adult donors. If this blood is received well, the researchers will attempt to give volunteers a transfusion of artificial blood made from stem cells extracted from umbilical cord blood donated by consenting mothers. These tiny transfusions will also give scientists time to study how long the synthetic blood is able to survive inside the human body.

Synthetic blood is the holy grail of the medical community. For years now, scientists around the world have been investigating how to manufacture red blood cells as both an alternative to donated blood and to treat patients with specific blood-related conditions. This artificial blood was created by scientists involved with the NHS and is part of an ambitious five-year research and development plan meant to advance the practice of blood transfusion, organ transplantation, and regenerative medicine.

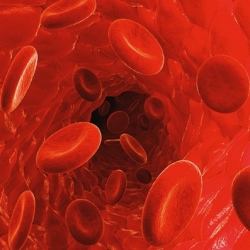

The blood is created by isolating stem cells, either extracted from umbilical cords or from the blood of adult donors, Newsmax reported. The stem cells are then cultured in nutrients that stimulate them to develop into red blood cells. Blood is composed of three components: red cells, plasma, and platelets. Red blood cells carry oxygen from the lungs to the rest of the body. Although all components are in need of donations, according to The Red Cross, red cell storage is often in short supply. Therefore, the need for an unlimited amount of red blood cells is most pressing.

The intention is not to replace blood donation but to provide specialist treatment for specific patient groups, Watkins explained. The immediate goal of the manufacturing of synthetic blood is to provide alternatives for individuals with blood conditions, such as sickle cell anemia and thalassemia, who need regular transfusions. Watkins hopes that scientists will soon be able to provide appropriate blood products specific to each patient’s need, a sort of customized blood transfusion.

More long-reaching plans of this NHS initiative include the creation of an unlimited supply of blood for blood banks. The current availability of donated blood does not match its need. According to the Blood Centers of the Pacific, only 37 percent of the American population is actually eligible to donate blood, and of this group, an estimated less than 10 percent actually do so regularly. Factors such as weight, past drug use, and having visited certain areas of the globe prevent many from donating their blood. The NHS hopes that synthetic blood will help to address the deficit availability of blood donations and also to keep blood’s price low.