Echolocation isn’t just for bats and dolphins, people can do it, too. Some blind people have learned to use echolocation to tell the size, density, and texture of objects around them, and researchers believe anyone can learn how. A subset of the blind population has figured out to use echolocation to navigate the world.

They make clicking sounds with their tongues or by clicking their fingers, and then perceive how those sounds bounce off objects around them. It’s a learned skill, and researchers think we’re all physiologically capable of picking it up, but it requires training and practice to master.

You might think echolocation would require exceptionally good hearing, but it doesn’t seem to. During a 2011 study, researchers gave two skilled blind echolocators a standard hearing test, and they only did about as well as two average sighted people.

In fact, echolocation doesn’t seem to be based on hearing, as we know it, at all. When a blind person clicks, that sound can bounce back from a nearby object in as little as three tenths of a millisecond.

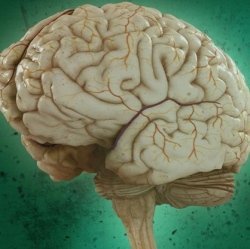

That’s too short to consciously hear the gap between sound and echo, but the parts of the brain involved in echolocation can not only perceive the gap, they can also read a wealth of information in it about the distance, size, shape, and nature of the object.

That’s because echolocation re-purposes parts of the brain that are normally used for vision. Neuroscientist Mel Goodale and his colleagues first realized this during their 2011 study, when brain imaging showed that in skilled echolocators, the visual area of the brain responded to echolocation the same way it responds to images.

When the researchers played clicks and echoes for sighted people and a group of blind people who didn’t know how to echolocate, however, the visual cortex didn’t respond. That seems to indicate that learning echolocation actually teaches the brain to replace one kind of input (vision) with another (echolocation).