Researchers are tackling the sixth-leading cause of death in the US, Alzheimer’s, with a study that intervenes decades before the disease develops. The school is joining approximately 90 institutions in North America, Europe and Australia in the Generation Study;

This study is testing a vaccine and oral medication to prevent or delay Alzheimer’s in older adults at increased risk for developing the disease. More than 70 USC researchers across a range of disciplines are dedicated to the prevention, treatment and potential cure of Alzheimer’s.

By focusing on prevention, the study is taking a different approach to halting a disease that affects 47 million people worldwide.

“One of the challenges in developing new medications for Alzheimer’s is that researchers tend to test medications on people with more advanced Alzheimer’s, and the medications are simply not proving to be effective,” says the study’s lead investigator at the Keck School, Lon Schneider, MD, professor of psychiatry and the behavioral sciences and professor of neurology. “By intervening 10 to 12 years before Alzheimer’s manifests, we may be able to stop it before it begins or delay the symptoms.”

Adults 60 to 75 years of age with normal cognition who are interested in participating must undergo genetic testing for the apolipoprotein e4 (APOE4) gene, which is associated with an increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s.

About half of people with Alzheimer’s disease carry the APOE4 gene, which can be inherited from either parent, Schneider says. About 25 percent of the population carries one copy of the APOE4 gene, and about two to three percent of the population carries two copies, having received one from each parent. To qualify for the study, participants must have two copies of the gene.

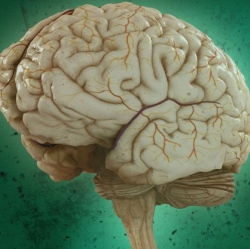

Qualifying participants may be randomized to either a vaccine, oral medication, placebo vaccine or placebo oral medication. Both the vaccine and oral medication target amyloid beta, the main component in amyloid plaques in the brain and a culprit in Alzheimer’s, in two different ways: The vaccine helps the body develop antibodies against amyloid beta, while the oral medication blocks an enzyme that creates amyloid beta. Participants may receive the study medications for five to eight years.

“If we are able to show that the vaccine or oral medication is effective at delaying Alzheimer’s among people at higher risk, then this would strongly imply that we are on the right track for developing treatments,” Schneider says. “If we can delay the onset of Alzheimer’s by five years, for example, the incidence of the illness would drop by half. It would also give individuals five more years without symptoms of the illness.”

Should the vaccine or oral medication prove to be effective in people with two copies of the APOE4 gene, then it would likely also be effective for other people at risk for Alzheimer’s, according to Schneider.

“Our clinician-scientists have been actively involved in clinical drug development for Alzheimer’s disease for more than 30 years,” says Rohit Varma, MD, MPH, dean of the Keck School. “This study is a reflection of our continued efforts to conquer one of the greatest health challenges of our time.”