Each year, U.S. hospitals collectively throw away at least $15 million worth of unused surgical supplies that could be salvaged and used to ease shortages, improve surgical care, and boost public health in developing countries, according to a report by a Johns Hopkins research team.

The report, published online earlier this month in the World Journal of Surgery, highlights not only an opportunity for U.S. hospitals to help relieve the global burden of surgically treatable diseases, but also a means of reducing the cost and environmental impact of medical waste disposal at home.

Surgical supply waste is nothing new, the researchers note, but add that their investigation may be one of the first attempts to measure the extent of the problem, the potential cost savings, and the impact on patients’ lives. While several organizations run donation programs for leftover operating room materials, such efforts would be far more successful if they were made standard protocol across all major surgical centers, the authors say.

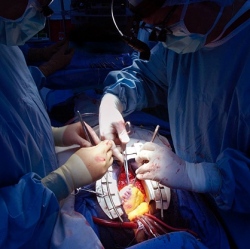

"Perfectly good, entirely sterile and, above all, much-needed surgical supplies are routinely discarded in American operating rooms," says lead investigator Richard Redett, a pediatric plastic and reconstructive surgeon at the Johns Hopkins Children’s Center. "We hope the results of our study will be a wakeup call for hospitals and surgeons across the country to rectify this wasteful practice by developing systems that collect and ship unused materials to places that desperately need them."

The staggering waste of surgical supplies, the researchers say, is rooted in the common practice of bundling surgical materials. The practice allows operating rooms to operate more efficiently, but once opened, everything in the bundle that is unused is thrown away.

"Such programs are acutely needed not only to help address serious needs in resource poor-settings but also to minimize the significant environmental burden at home institutions," says study co-author Eric Wan, a recent graduate of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine currently doing postdoctoral training at the National Institutes of Health. "This really is a win-win situation."