It’s an oft-repeated idea that blind people can compensate for their lack of sight with enhanced hearing or other abilities. The musical talents of Stevie Wonder and Ray Charles, both blinded at an early age, are cited as examples of blindness conferring an advantage in other areas.

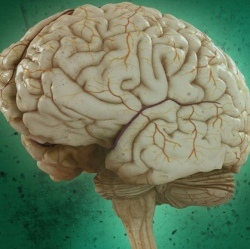

It is commonly assumed that the improvement in the remaining senses is a result of learned behavior; in the absence of vision, blind people pay attention to auditory cues and learn how to use them more efficiently. But there is mounting evidence that people missing one sense don’t just learn to use the others better. The brain adapts to the loss by giving itself a makeover. If one sense is lost, the areas of the brain normally devoted to handling that sensory information do not go unused, they get rewired and put to work processing other senses.

A new study provides evidence of this rewiring in the brains of deaf people. The study, published in The Journal of Neuroscience, shows people who are born deaf use areas of the brain typically devoted to processing sound to instead process touch and vision. Perhaps more interestingly, the researchers found this neural reorganization affects how deaf individuals perceive sensory stimuli, making them susceptible to a perceptual illusion that hearing people do not experience.

These new findings are part of the growing research on neuroplasticity, the ability of our brains to change with experience. A large body of evidence shows when the brain is deprived of input in one sensory modality, it is capable of reorganizing itself to support and augment other senses, a phenomenon known as cross-modal neuroplasticity.

Understanding how the brain rewires itself when a sense is lost has implications for the rehabilitation of deaf and blind individuals, but also for understanding when and how the brain is able to transform itself. Researchers look to the brains of the deaf and blind for clues about the limits of brain plasticity and the mechanisms underlying it. So far, it appears that some brain systems are not very plastic and cannot be changed with experience.

Other systems can be modified by experience but only during particular sensitive periods (as is the case with language acquisition). Finally, some neural systems remain plastic and can be changed by experience throughout life. Discovering factors that promote brain plasticity will impact several areas: how we educate normally developing as well as blind and deaf children; rehabilitation after brain injury; and the treatment (and possible reversal) of neurodegenerative diseases and age-related decline.