Researchers have found evidence of a unique “signature” that may be the “missing link” between cognitive decline and aging and that may in the future lead to treatments that can slow or reverse cognitive decline in older people. scientific dogma held that the blood-brain barrier prevents blood-borne immune cells from attacking and destroying brain tissue.

Yet in a long series of studies, Schwartz showed that the immune system actually plays an important role both in healing the brain after injury and in maintaining the brain’s normal functioning. Her team have found that this brain-immune system interaction occurs across a barrier that is actually a unique interface within the brain’s territory: the choroid plexus. This structure is found in each of the brain’s four ventricles, and it separates the brain’s blood from the cerebrospinal fluid.

“The choroid plexus acts as a ‘remote control’ for the immune system to affect brain activity,” Schwartz explains. “Biochemical ‘danger’ signals released from the brain are sensed through this interface; in turn, blood-borne immune cells assist by communicating with the choroid plexus. This cross-talk is important for preserving cognitive abilities and promoting the generation of new brain cells.”

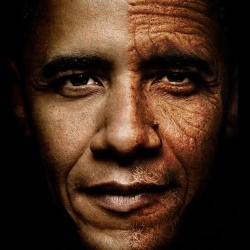

This finding led Schwartz and her group to suggest that cognitive decline over the years may be connected not only to one’s “chronological age,” but also to one’s “immunological age,” that is, changes in immune function over time might contribute to changes in brain function that are not necessarily in step with the count of one’s years.

To test this theory, Schwartz and research students Kuti Baruch and Aleksandra Deczkowska teamed up with Amit and his research group. The researchers used next-generation sequencing technology to map changes in gene expression in 11 different organs, including the choroid plexus, in both young and aged mice, to identify and compare pathways involved in the aging process.