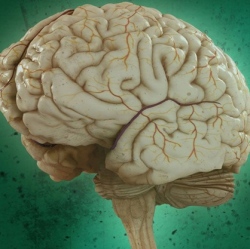

The protective sheath surrounding the brain’s blood supply, known as the blood-brain barrier, is a safeguard against germs and toxins. This prevents existing drugs that could potentially be used to treat brain cancer or Alzheimer’s. Scientists want to unchain the gates of this barrier. Now a new study shows it’s been done in cancer patients.

Alexandre Carpentier, a neurosurgeon at the Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris, used ultrasound to open the blood-brain barrier in patients with recurrent glioblastoma, the most common and deadly tumor originating in the adult brain, allowing for delivery of chemotherapy that would otherwise reach the tumor in minuscule amounts. The preliminary results of the early phase clinical trial were reported Wednesday in Science Translational Medicine.

The procedure works by first injecting microbubbles into the bloodstream and then using a device implanted near patients’ tumors to send ultrasonic soundwaves into the brain, exciting the bubbles. The physical pressure of the bubbles pushing on the cells temporarily opens the blood-brain barrier, letting an injected drug cross into the brain.

“People for years have been trying to open the blood-brain barrier,” said Neal Kassell, founder of the Focused Ultrasound Foundation. The device, called SonoCloud, was implanted and used on 15 patients during monthly chemotherapy with no ill effects after six months.

Although this is the first published study using ultrasound to open the blood-brain barrier in humans, it is not the first study to hit the news. In November, a team at the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto announced the start of a clinical trial to open the blood-brain barrier using ultrasound in a single brain cancer patient. Carpentier’s trial, on the other hand, began in July 2014, and Kassell said the French study “is the first time they’ve shown the safety of repetitively opening the blood-brain barrier in humans.” Both clinical trials are ongoing.

The Sunnybrook trial used a focused ultrasound device, which is good for pinpointing localized cancers. In contrast, SonoCloud emits ultrasound more diffusely, which is useful for glioblastomas that blend into surrounding brain tissue. “It seems a little more aggressive to implant something,” Carpentier said, but the wider-ranging ultrasound opens a larger swath of the blood-brain barrier. This enables chemotherapy drugs to reach cancer cells around the periphery of the main tumor, hopefully reducing the chance that the cancer will grow back.

Carpentier, who invented SonoCloud and founded its parent company, CarThera, says the most surprising part was the patients’ response to the implant. “The patients don’t feel anything when we emit ultrasound,” he says. “And they actually don’t complain about it. It was set up in the protocol to remove it after six months, but patients don’t want to remove it.”

He is now designing the next phase of the clinical trial to determine how much more effective the chemotherapy is with an opened blood-brain barrier. Carpentier says the technology is a “huge opportunity” to improve treatment of many diseases. He is also beginning work on a trial with Alzheimer’s patients, since studies in mice have showed that merely opening the blood-brain barrier with ultrasound helps remove the amyloid-β protein thought to be responsible for Alzheimer’s without using any drugs.

The ultimate goal of ultrasound therapy is “to be able to repetitively and reversibly open the blood-brain barrier in a non-invasive, targeted, and focused manner,” Kassell says. “This is one more step toward that goal.”