Dubbed “Zombie cells,” senescent cells slowly accumulate with age or with cancer treatments. The cells lose their ability to perform normal functions.

Instead, they leak a toxic chemical soup into their local environment, increasing inflammation and damaging healthy cells. Over a decade of research has shown eliminating these cells with genetic engineering or drugs can slow down aging symptoms in mice.

In one early clinical trial, cleaning out zombie cells with a combination of drugs in humans with age-related lung problems was found to be safe. Battling senescent cells isn’t just about improving athletic abilities.

To Carlos Anerillas, Myriam Gorospe, and their team at the National Institutes of Health in Baltimore, therapies have yet to hit zombie cells where it really hurts. In a study in Nature Aging, the team pinpointed a weakness in these cells: They constantly release toxic chemicals, like a leaky nose during a cold.

Zombie cells use a “Factory” inside the cell to package and ship their toxic payload to neighboring cells and nearby tissues. The new study nailed down a protein pair that’s essential to the zombie cells’ toxic spew and found an FDA-approved drug that inhibits the process.

Each cell is a bustling city with multiple neighborhoods. The ER packages proteins and delivers them to internal structures, the cell’s surface, or destinations outside the cell.

Normally, the ER helps cells coordinate their responses with neighboring tissues-say, allowing blood to clot after a scrape or stimulating immune responses to heal the damage. Faced with so much damage, normal cells would wither away, allowing healthy new cells to replace them in some tissues like the skin.

As long as the harm stays below a lethal level, the cells live on, expelling their deadly brew and harming others in the vicinity. These traits make zombie cells a valuable target for anti-aging therapies. Most have relied on existing knowledge or ideas about how zombie cells work.

Here, the team disrupted every gene in the human genome to pinpoint those that eliminated zombie cells. The screen found a protein pair critical for senescent cell survival.

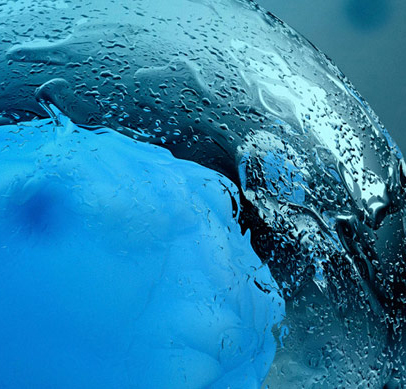

In several zombie cell cultures with the protein pair, the drug drove senescent cells into apoptosis-that is, the “Gentle falling of the leaves,” a sort of cell death does no harm to surrounding cells. Digging deeper, the drug seemed to directly target the zombie cells’ endoplasmic reticulum-their shipping center.

Cells treated with the drug couldn’t sustain the delicate multi-layered structure, and it subsequently shriveled into a shape like a wet, crumpled paper towel.

“A shrunken ER triggered a metabolic crisis” in zombie cells, explained Anerillas and Gorospe.

As we age, immune cells often enter the lungs and cause damage. Decreased numbers of senescent cells dampened inflammatory signals, which could explain the rejuvenating effects, explained the team. Verteporfin also stopped a “Guardian” protein that protects senescent cells from death, further triggering their demise.

Tapping into a zombie cell’s unique vulnerabilities is a new strategy in the development of senolytics. The endoplasmic reticulum isn’t the only cell component in the biological waste factory. Other cellular components that generate senescent cell poisons could also be blocked and help remove the cells themselves.

It’s a promising alternative to existing methods for wiping out senescent cells.